By Benjamin Franklin Martin

The extinction of species is part of the natural order, but to experience such extinction not through the fossil record but through photographs—and thus in roughly the last century and a half, when man’s pressure upon other species has become increasingly heavy, is sobering. Errol Fuller writes that these photographs are “evocative and moving records of creatures that are gone.” Yes, gone: most often because of habitat destruction, sometimes through hunting, occasionally when evolution has left them incapable of adjustment to change.

Two small flightless birds, the Wake Island Rail (Gallirallus wakensis) and the Layson Rail (Porzana palmeri)) failed to survive the devastation of World War II in the Pacific. The large flightless Atitlán Giant Grebe (Podilymbus gigas) of the Guatemala highlands could not withstand the effects of changing habitat, pollution, civil war, and dilution through hybridization. It was last seen in 1978. The swampland of the Pink-Headed Duck (Rhodonessa caryophyllacea) along the lower Ganges River in India was drained, and it could not survive, refusing even to breed in captivity, the last dying in 1936.

The Heath Hen (Tympanuchus cupido cupido), once wide-spread over the eastern United States, declined before the spread of human settlement and a taste for its flesh. The last of its kind, “Booming Ben,” died on Martha’s Vineyard in 1932. The Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis), the only species of parrot indigenous to this country, had a similar range but after hunting drastically reduced its numbers, the remaining birds died out because they had evolved to live only in large flocks. The last Carolina Parakeet, Incas, died at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1918. The Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) is the supreme example, its numbers in the billions at the beginning of the nineteenth century but extinct in the wild by 1900. The last one, Martha, died in 1914, also at the Cincinnati Zoo. Like the Carolina Parakeet, it could only survive in large flocks.

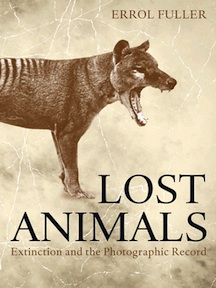

The Thylacine, sometimes called the “Tasmanian Tiger” (Thylacinus cynocephalus) was a marsupial carnivore resembling a striped wolf that once ranged over New Guinea, Australia, and Tasmania. In modern times, it was confined to Tasmania, where it was hunted to extinction through a bounty designed to protect sheep herds. The last Thylacine died in 1936 at a Tasmanian zoo. Hunting, this time for sport, extinguished the Bubal Hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus), a magnificent antelope found north of the Sahara Desert. The last herd, some fifteen, was sheltering within the Atlas Mountains in 1917 when it was discovered. As the concluding sentence to Lost Animals, Fuller writes, “All but three were slaughtered by a single hunter.” Sobering indeed.

Benjamin Franklin Martin (ΦΒΚ, Davidson College, 1969) is the Price Professor of History at Louisiana State University and a resident member of the Beta of Louisiana Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.