By Svetlana Alpers

There seems no need to worry about painting today. There are some hugely famous painters who famously sell their works at huge prices. And many young artists are deciding to cast their fate with painting. But something has changed— as Wayne Thiebaud puts it at one point in this book, the idea today is to be an artist not a painter. Modern artists want to enter the front door, not the tradesman’s entrance. One could say that the notion of the artist as intellectual/theorist was already in place in seventeenth century Italy. But Thiebaud is focused on rejecting the idea of being an “art employee”—someone who works for the current art scene and all that involves. He became a professor at University of California, Davis, remained there and refused to be represented by any New York gallery.

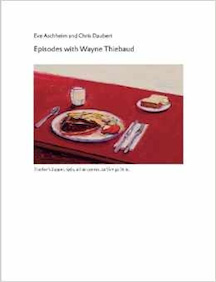

If you want to get a measure of painting and its possibilities, this book of four conversations conducted over three years with a master painter (born 1920) is the place to go. The pair of interviewers were Thiebaud’s students in the 80s. They describe their master as part workman, part intellectual, part intellectual, part athlete [he plays tennis], part educator and fearless iconoclast. All of that and more come out as he talks.

There are technical things: the choice to paint from or is it against a white back ground; the continuous recourse to the skill of drawing as a way to know things in the world and a necessary basis; the insistence on the plane as essential to all painting. There are wise words about painters he loves and why. It is not surprising that Hopper, a fellow American vernacular realist, is high up there. More surprising perhaps is the taste for Ad Reinhardt who teaches us to see in shadow—a point which Thiebaud illustrates by framing a dark portion of a photo of Hopper’s Manhattan Bridge Loop with his fingers. And then there is de Kooning, an artist like himself trained in commercial art, who, on Thiebaud’s account, never rejected those skills while also tending to keep them at bay. He is insistent about what he sees (literally sees) as the terminal nature of much abstract painting—instancing Robert Ryman, whom he admires, versus Vermeer in that. What you can take from Pollock or Barnett Newman is much less, so he argues, than you can take from Vermeer or Velázquez. He is critical of Pollock whom, unfashionably, he describes as un-locate-able—a loss of edge, unable to draw—yes, he changed the boundaries but of not great interest as a painter.

What Thiebaud has to say often goes against the grain. He makes one think about painting and want to go back and look. He is for small works not large. I have to say I haven’t seen many large paintings that I like very much. The reach of the arms is, for him, the optimum scale for a painting. He can be wonderful on the art of the past: the marvelous thing about Van Gogh is that his drawings are so powerful in painting: he is really most of the time drawing in painting. Or quite differently, remembering the Vermeer show at the Met, I’ve never been at an exhibit with a lot of people when it was so quiet. That was fascinating. People were just hushed. The conversation concludes with Velázquez: It’s like watching the Wimbledon of permier coup painting, . . I think he was so focused in so many ways at the same time somehow. He almost eluded the instant and could take longer with awareness or something with that eye. I don’t know. It’s a real mystery how he could come up with it. I don’t know. It was such a joy to see it.

The conversations in this book are not about art and politics which is a major pre-occupation of artists and curators and critics these days. It is about painting from one painter’s point of view and about looking. There is a marvelous moment when Thiebaud bursts out and says, It feels strange to be talking about painting. . .when you’re painting you are thinking about maybe a hundred things and when you’re talking you say only one thing.

Svetlana Alpers, an artist, critic and renowned art historian, is professor emerita of the history of art at the University of California, Berkeley and a visiting scholar in the Department of Fine Arts at New York University.