By Svetlana Alpers

Did Grace Hartigan paint fascinating paintings? Did she have a fascinating life? I fear the answer to both questions might well be no. But the combination of her life and her art as told in this biography makes for a fascinating book which fully justifies the author’s passion for her subject. The gerundives which serve as chapter titles (Dreaming Searching, Struggling and so on) are a writerly way to highlight the restless (one might also say relentless) ambitions of a remarkable woman.

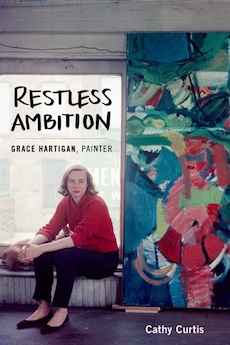

The book opens with a meeting with Hartigan (described as “earthy and voluble”) in Los Angeles in 1988 when Curtis was a cultural reporter and art critic for the LA Times. And it fast forwards to the stunning impression (“slashing blocks of vivid color”) made on her by Hartigan’s large (7 x 6 foot) 1957 painting titled Shinnecock Canal in the 2010 Abstract Expressionism show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. (The publisher has been generous with color plates so that you will get a sense of the paintings if you do not know them already.)

It was rare for a woman to make it big in the New York art world of the fifties. And Grace Hartigan (1922-2008) was the odd woman out among the few successful woman painters of her time. Helen Frankenthaler and Joan Mitchell were born to wealth and privilege. They went to fancy colleges. They had connections. Not so Hartigan. She was born in Newark, New Jersey and grew up in Millburn, Her parents were quarrelsome. Her mother did not love her. It is a great strength of Curtis’ book that she sets out the social conditions of the world in which Hartigan started and then of the artists’ world she made her way into in New York. The reader finds herself immersed in the now distant American life of those mid-century decades.

Graduating from high school, Hartigan worked in an insurance company,married a fellow worker with whom she headed to Los Angeles where they both enrolled in an adult education public school art class, had a child, returned to New Jersey, from where her husband left for the war. Hartigan put her son in day-care, met an artist who had a school in Newark moving with him to New York in 1945 where she took up a job drafting at a Diamond Match Company in White Plains.

So began her life in New York where among early friends were the Milton Amorys, Mark Rothko, and Adolph Gottlieb. By this time her son was living with his grandparents. She saw him only occasionally for the rest of his life. And to cap that off she kept her distance from his children. Curtis usefully points to the number of women artists and writers who gave birth to a child and chose to put it out of their lives. To which one might add the number – like Mitchell and Frankenthaler – who chose not to give birth. The conditions of being a painter who was a woman (Hartigan rejected being thought of as a woman painter) were challenging. Though Hartigan was never long without husband or lover, as a painter she resisted being secondary to a man which was the role accepted by most of the women painters she knew.

One is surprised by the large amount of life experience and the small amount of experience in looking at and learning how to make art Hartigan had. Indeed, one might say her art was always rooted and driven by her life. And things moved quickly. In 1948 she first saw works by Jackson Pollock. Through him she came to know Willem de Kooning. She had come upon the roots of her own style to be. In 1950 (she was then twenty-eight) a painting of hers was chosen by none other than Clement Greenberg, the leading critic, and Meyer Schapiro, the leading art historian, for a group show at the Kootz Gallery.

The 50s were her greatest years as an artist and Curtis focusses much of the book on them: we learn the ins and outs of her close relationship with the poet Frank O’Hara, the qualities of the Cedar Bar and various artist clubs, the crisis it was for her to forsake pure abstraction for representational passages. In the telling, it seems a rich but also a frantic life – the satisfactions but also the disappointments were great. Hartigan lived fully and took things hard. She also drank too much.

You have to read the book to experience the dizzying sequence of pictorial discoveries (a Matisse show, Velázquez at the Metropolitan Museum), theatrical performances, exhibitions, parties, and sheer hard work that made for her success. The energy of the writing in the book matches the energy it took to lead such that life. Every now and then I found myself stepping back in amazement at it all.

And then the collapse or “Swerving” as Curtis titles it. Unexpectedly, Grace succumbed to and then married a famed medical scientist at John Hopkins who loved art and Grace. She moved to Baltimore. Cut off from New York, she taught at the Maryland Institute College of Art. Eventually, her work suffered. And her style was no longer current. Her husband sickened and died from the self-administered testing of an experimental drug. Grace lived on until 2008. I am being too brief. Read this book to learn of life as lived and art as made by a remarkable woman.

Svetlana Alpers, an artist, critic and renowned art historian, is professor emerita of the history of art at the University of California, Berkeley and a visiting scholar in the Department of Fine Arts at New York University.