By Colin Rafferty

Perhaps we, as humans, have an inclination to unearth everything done by the artists we love, even if the artist may not have necessarily wanted these things brought into the light of day. Recent new books by authors as varied as Dr. Seuss and Harper Lee have raised questions about authors’ rights to control their own output against the audience’s desire for more work by their beloved artists, and the possibility always exists that the new work can diminish the power and beauty of the old work.

In this light, it would be easy to dismiss the publication and exhibition of the notebooks of American artist Jean-Michele Basquiat, whose graffiti and graffiti-inspired paintings helped shape the art scene of 1980s, and who died of a heroin overdose in 1988 at the age of 27, as a chance to widen the market for Basquiat, whose paintings have begun to command prices in the tens of millions. However, the notebooks are more than a simple cash-grab or attempt to increase the number of extant works by the artist; they are a crucial exploration of the artist’s mindset, and, more importantly, a stretching of the metaphysical questions of what art is and what it can do.

In a brief introduction, Larry Warsh, editor and custodian of the notebooks, argues that the notebooks are not simply rough drafts of later, larger works; instead, “they’re a summary of his most carefully articulated, intimate, and poetic thoughts” and “a separate practice, distinct from the work he did on the street or in the studio.” Some pages display drawings of figures in Basquiat’s familiar style—crowns, tepees, and skeletal bodies all appear here—but the vast majority of pages feature words, usually printed in Basquiat’s distinctive all-caps block handwriting. Occasional narratives appear (“The motorcycle pulls up to the road diner man gets off orders a hamburger and egg hero,” begins one), but more often the narratives are suggested by a fragment or two (“the editors arrested/magazine shut down”) or are entirely absent, with only lyrical bits and pieces, even a single word.

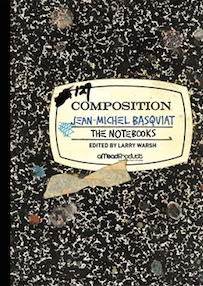

The eight notebooks that comprise the book are reproduced lovingly by Princeton University Press; the book’s cover, made of pasteboard, recreates the familiar black-and-white composition notebook covers that Basquiat used, and the interior pages are perfect recreations of the original pages, down to coffee stains, ink smears, and bled-through markers and oil sticks that create ghostly afterimages on the backs of pages. Even though Warsh insists that the “notebooks are not sketchbooks, and they weren’t intended for doodling,” they nevertheless bring a warm casualness with them; as the reader explores these notebooks, she will discover evidence of Basquiat’s process—crossed-out lines and repeated ideas, signs of the artist working through his ideas carefully and deliberately. Ephemera of New York City in the 1980s comes through as well—movie times and phone numbers, appointment times and travel plans all appear on pages here (when the notebooks were exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum this year, the museum included the young artist’s membership card to the Museum, a fine addition to the humanity these notebooks display).

Ultimately, readers’ reactions to this volume will rest upon how they regard contemporary art. One page simply reads “ART.” If, upon reading this, you scoff at the idea that someone might go to a museum to see this, or pay thirty dollars to own a recreation of this notebook, then the Notebooks are not for you. But if you see this page and begin thinking about how we create art, what art might be, and what role the artist plays in our society, then you will find much to consider in Basquiat’s Notebooks. This beautiful book does not diminish the artist or his art by flooding the market with subpar work; instead, it expands our understanding of what this artist created in the too-short time he spent at work.

Colin Rafferty (ΦBK, Kansas State University, 1998) teaches nonfiction writing at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Mary Washington is home to the Kappa of Virginia Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.