Shortlisted for the 2019 Christian Gauss Award

By David Madden

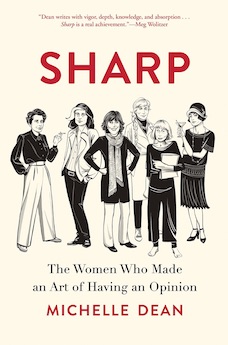

In Sharp: The Women Who Made An Art of Having An Opinion, Michelle Dean introduces ten unforgettable, sharply opinionated women unfamiliar to some readers and reminds those who do remember them just how sorely we are in need this very hour of more women like them.

Award-winning contributor to major magazines, Dean may move readers to feel that she knew each of these women as well as they knew each other, and her own lucidity and wit earn her a place among such women.

Although generally supportive of one another, most of these women sharpened their wits in both friendly and adversarial interaction with each other. Rebecca West championed the writings of Zora Neal Hurston, and Mary McCarthy and Hannah Arendt were long-time friends, while McCarthy and Lillian Hellman famously went at each other’s throats.

Dorothy Parker’s one-liners, such what she said looking at F. Scott Fitzgerald in his coffin—“The poor son-of-a-bitch!”—and her razor-sharp poetry made her one of the most famous women of her time.

“Resumé”

Razors pain you;

Rivers are damp;

Acids stain you;

And drugs cause cramp.

Guns aren’t lawful;

Nooses give;

Gas smells awful;

You might as well live.

—Dorothy Parker, 1925

Parker’s poignant short stories also deserve discovery and rediscovery. My knowledge of most of these women as their fame grew and my reading about them in Dean’s book give me good reason to say that their lives and works are rather prefigured in Dorothy Parker’s.

I reviewed Susan Sontag’s first novel, The Benefactor, in 1963 and followed her innovative fiction and controversial nonfiction until her death in 2004. My interest in Sontag and her work was a fine pleasure that Dean reactivated.

As I waited for foreign movies to begin in Pauline Kael’s theater in Berkeley in the mid-1950s, I read her distinctive notes, which inclined me to review her collections of controversial reviews, beginning with I Lost It at the Movies. Dean enables us to see Kael clearly.

I imagine readers who will be delighted with Dean’s character studies of four other, more recent sharp women: Joan Didion, Renata Adler, Janet Malcolm, and Nora Ephron.

Some of these mostly New York Jewish women refuse to be called feminists, but ironically, their sharp opinions and independent lifestyles make direct and indirect contributions from the 1930s to the present to women’s causes.

Given my own personal immersion in news of the lives of these ten women and in their works, I demanded just and apt appraisal of them as I began Michelle Dean’s book. Her knowledge, empathy, intellect, and uncommonly lively, witty, and lucid style provided an experience I hope many other readers will appreciate as fully as I did.

David Madden (ΦBK, University of Tennessee, 1979), author of many works of fiction and nonfiction, has just finished an innovative biography of James M. Cain, a memoir of his mother, and My Intellectual Life in the Army.