By Allen D. Boyer

“What any biography of Mark Twain demands is his inimitable voice,” maintains Ron Chernow (ΦBK, Yale University). “Whether Mark Twain was our greatest writer may be arguable . . . but there’s little question that he was our foremost talker.”

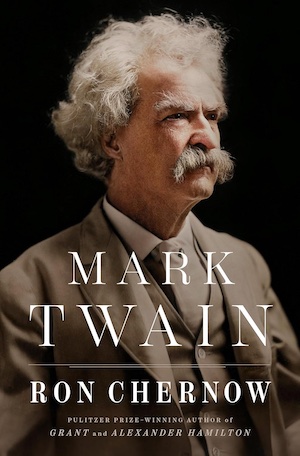

The Mark Twain of popular culture—folksy, witty, avuncular; “a humorous man in a white suit, dispensing witticisms with a twinkling eye”—is here. Chernow always offers more.

“In a country that prides itself on can-do optimism, Mark Twain has always been an anomaly: a hugely popular but fiercely pessimistic man, the scourge of fools and frauds. . . . The sources of his humor are deadly serious, rooted in a profound critique of society and human nature that gives his jokes their staying power.”

In sheer volume, the archive through which Chernow has worked rivals the files of the Pentagon. “Some twelve thousand letters written by Mark Twain and his immediate family and nineteen thousand written to them or about them” form the core of the Mark Twain Papers and Project Archive at Berkeley; beyond that lie more than thirty published books, fifty surviving notebooks, and several hundred unpublished manuscripts. This tally omits entirely the massive clippings file generated by Twain’s travels and lectures.

Where the record is thickest, Chernow’s narrative is densest and most revealing. There is little on Hannibal, Missouri, where the author began life as Samuel Langhorne Clemens (45 pages in a book of nearly 1200). The story broadens in Nevada, where frontier journalism had the volatility of a Twitter firefight, and Sam Clemens began publishing as Mark Twain. (“It was a place of sin, loose women, whiskey and gambling,” he recalled; “it was no place for a good Presbyterian, and I did not long remain one.”) Already, his drive and ambition had been noted. “Mark was the laziest man I ever knew in my life, physically,” a colleague wrote. “Mentally, he was the hardest worker I ever knew.”

Twain’s awe at U.S. Grant’s talent and stamina is well-known; Chernow highlights Twain’s early sketches of Civil War generals and Reconstruction politicians. Also familiar is Twain’s disastrous involvement with the Paige Compositor (a typesetting machine of 18,000 parts, which the Linotype process rapidly eclipsed). Chernow makes clear that this debacle was more than financial; it absorbed Twain’s energy for fifteen years and more.

Twain was happy in his marriage to Livy Langdon, which lasted thirty-four years. His broader family life, Chernow sums up, “was shadowed by a staggering number of calamities.” Mark and Livy’s daughter Jean suffered hellishly from epilepsy, and died of a grand mal seizure, aged twenty-nine. Their daughter Susy, who died even younger, they had removed from Bryn Mawr when her friendship with a classmate turned romantic. Outside Florence, in a villa where the family was summering, Livy died of a heart attack. A third daughter, Clara, became a concert singer, and survived her parents.

The characters in this book are implausibly varied. (“Truth is stranger than Fiction,” Twain commented, “but it is because Fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities; Truth isn’t”). They range from Kaiser Wilhelm, who disliked Twain’s contention that Civil War pensions had degenerated into a scheme for buying votes, to Warner McGuinn, a black student at Yale Law School whose studies Twain financed, and who lived to become a mentor of Thurgood Marshall. Hidden in plain sight is the earnest, gifted William Dean Howells, Twain’s editor, publisher, and co-author, who must have realized that he would be remembered for playing straight man to a white-garbed, wild-haired genius.

The tide of quotations does more than document Twain’s public wit and personal struggles; it supplies a panorama of the age that his energy brightened. “Mr. Twain may be called the Edison of our literature,” the San Francisco Chronicle wrote, and a marvelous photo shows Twain, with his shock of white hair, in a dark room lit only by one of Nikola Tesla’s mad-scientist devices.

In assessing Twain’s attitude toward race, Chernow balances the ambivalence of Huckleberry Finn (perhaps too comfortable with a world where black slaves labor and white men rule) with the scathing melodrama of Pudd’nhead Wilson. Twain’s last major novel, the book is the story of a mixed-race child (one-thirty-second part black) swapped at birth with the newborn son of his mother’s master; the boy raised as a white aristocrat grows up “to be brutal and domineering, while the white child brought up as enslaved is meek and compassionate.” Chernow concludes: “More than likely, Twain was illustrating his deterministic view that we are all creatures of roles assigned to us by society.” Southern reviewers hated the book; Toni Morrison praised it.

Twain set epigrams at the head of each chapter in Pudd’nhead Wilson. He retailed these and other witticisms on calendars and postcards—but they epitomize his penchant for deadly serious jokes. “Always do right; this will gratify some people and astonish the rest.” “If you pick up a starving dog and make him prosperous, he will not bite you. This is the principal difference between a dog and a man.” “Man is the only animal that blushes. Or needs to.” “Man is the only Slave. And he is the only animal who enslaves.”

Here, in Twain’s tone, there again is more. On the centennial of Huckleberry Finn, Norman Mailer imagined Twain’s greatest book appearing as a modern first novel. Inescapably, he admitted, Hemingway’s influence would stand out. “We know that we are not reading Ernest only because the author, obviously fearful that his tone is getting too near, is careful to sprinkle his text with ‘a-clutterings’ and ‘warn’ts.’” And Mailer pointed out the sweep of Twain’s other influences:

The author of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn had obviously been taught a lot by such major writers as Sinclair Lewis, John Dos Passos and John Steinbeck; he had certainly lifted from Faulkner and the mad tone Faulkner could achieve when writing about maniacal men feuding in deep swamps; he had also absorbed much of what Vonnegut and Heller could teach about the resilience of irony. . . . In places one could swear he had memorized The Catcher in the Rye.

This volume, as Chernow recognizes the biography of Mark Twain must be, is a book of bons mots. And yet the nation’s best-known minter of epigrams remains the most eloquent exponent of the American vernacular.

Allen D. Boyer (ΦBK, Vanderbilt University) grew up in Mississippi and writes in New York City. Vanderbilt University is home to the Alpha of Tennessee Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.