By Caroline Eng

It is 3:34 in the morning.

A class of Fordham undergraduates sits around a large conference table amidst an ocean of empty coffee cups and pizza crusts. They have just finished reading the entirety of John Milton’s Paradise Lost.

The students shake Professor Frank Boyle’s hand as they stumble out the door. Each one has had a turn grappling with the complicated language. Gradually, over the course of nine hours reading the twelve long books, their voices grew from fumbling to confident.

This is the latest in a long line of Boyle’s Milton classes to take on the “all-night reading,” a tradition that he has perfected through years of trial and error. In its most recent form, the reading takes place on a Thursday night starting at 6pm. Although it is optional, the whole class has sacrificed their night to participate.

The practice of reciting poetry is as old as the medium itself. Historically, poetry was intended to be read aloud. Epic poems such as the Illiad and the Odyssey, predating Milton by over a thousand years, grew through an oral tradition. They were passed down from person to person for hundreds of years, fluid and indefinite, before they were finally immortalized in writing.

Oral poetry was especially essential in a world where widespread literacy was unknown. In 2016, however, students of literature sit with print books or PDF files and consume these ancient works in silent solitude.

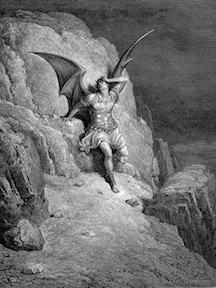

Unlike the Odyssey, Paradise Lost was not passed through the masses from bard to bard, slowly growing through an oral tradition. Even so, in its first form Paradise Lost was recited aloud. John Milton, who was fifty-one when the epic was finally published, composed it in a state of near total blindness. Unable to write, he dictated the poem to his three daughters—Deborah, Annie, and Mary—and never saw the finished product written down. He recited it to them like a Homeric bard.

In this undergraduate classroom, between the hours of 6p.m. and 3a.m., Boyle’s students relive a piece of the ancient oral tradition and hear the words as Milton’s daughters did in 1667. The all-night reading, Boyle says, is about giving students a sense of ownership over a work of incomprehensible scope. After the reading, he reports that students invariably turn in better, more daring papers. The in-class discussions are more lively and engaged. The students have learned how to hear the music of the language by trying to sing it out loud. To read all twelve books consecutively, Boyle says, has surprised even him by revealing the epic dramatic arc of the poem as a whole. The all-night reading introduces students to the theatrical sweep of the poem’s narrative, the distinct voices, and moments of humor that they would otherwise miss.

To read poetry aloud is to experience it in a new way. While it was once the primary vessel for poetry, verbal recitation now only exists on a stage. “Open-mic nights” do take place in coffee shops and church basements across the nation, but they rarely feature the works of a seventeenth-century epic poet. It is more than likely that, on a Thursday night in March, in the wee hours of the morning, these liberal arts undergraduates are the only voices speaking words that so richly deserve to be heard.

Caroline Eng is a junior at Fordham College at Lincoln Center majoring in English. Fordham is home to the Tau of New York Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.