By Meghan Barrett

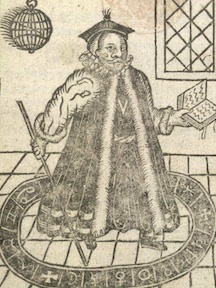

Science as a subject of theater has a history extending back to Elizabethan era, when Doctor Faustus by Christopher Marlowe was first performed. Theatrical representations of science, of course, have evolved to reflect changes in scientific conventions, from Marlowe’s alchemy and necromancy to physics and the scientific method as displayed in Bertolt Brecht’s The Life of Galileo written in the early 1940s. Science plays have been relatively rare and scattered in the history of drama, but they seem to be gaining popularity once more in contemporary theater.

Coinciding with this new-found popularity is the critically important role science-theater hybrids play in increasing cultural awareness of science, research, and ethical concerns related to emerging scientific fields. Perhaps the best example of this is Copenhagen by Michael Frayn, a 1998 play that focuses on the 1941 meeting of Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg with more than 300 performances at the National Theater in London alone. This incredibly popular play brought the ethical concerns surrounding the development of the atomic bomb to the forefront of a global consciousness, asking questions about the morality of each scientist in developing the bomb and what happens when science becomes political. The power of science plays to revolutionize the cultural understanding of a scientific issue, to teach science, and to involve the public in scientific debate is unparalleled by other science-creative writing hybrids.

There are several reasons why theater is the only medium to gain this incredible cultural power when it comes to science. The most obvious reason may be the human element; seeing a real, physical person engages an audience in the emotive sway of an ethical dilemma through body language and other non-verbal cues more influential than words alone. The science is also more accessible to the audience when acted out and visualized. While films also have real people in them, they lack the urgency of theater. The action of the play is continuous and occurs in real time with no second takes, just like real life interactions.

Theater is also a unique medium in relation to science in that it parallels the scientific process so completely. Just as a play cannot be paused, an experiment cannot be paused (nor can the dissemination of knowledge be paused after something has been discovered, a central idea in many science plays). Theater parallels the conversational aspect of science as a multi-level, continuous dialogue between different disciplines, technologies, laboratories, and eras, as it is a dialogue between characters, the actors and their characters, within each character, and between characters and the audience.

Just as a scientist has control over their experiments, drama gives the audience control over the play. In films, the audience gets only the cuts, camera angles, and close-ups that the director wants it to see, although the audience is aware of the rest of the scene occurring outside its field of view. However, every audience changes the atmosphere of a theatrical performance; novels and films are not affected by their readers/viewers the way actors change in relation to an audience. In a live performance, each scene is shown to the audience in full; each audience member can choose which face to look at, which part of the scene they want to focus on.

Science, when wielded by powerful political and economic institutions without the knowledge or consent of the general public can create powerful and disturbing new realities, such as the forced sterilization of working class women or genetically engineered proprietaries like GMOs that can critically harm the environment. The public has a responsibility to debate the ethical issues surrounding the most recent scientific advances in order to hold powerful institutions and corporations accountable for their misuse. Due to the unique relationship theater has with science, there is no medium as perfectly suited to tackle the personal responsibilities and moral quandaries of science in the modern world.

Image: A section of the cover art from a 1620 printng of Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus.

Meghan Barrett is a senior earning her BS in biology and creative writing at SUNY Geneseo. She is president of Alpha Delta Epsilon regional sorority and a proud member of the Alpha Delta of New York Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa at SUNY Geneseo.