By Adam Reece

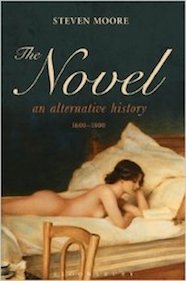

Steven Moore, author, literary critic, editor, bookseller, and avid reader recently received Phi Beta Kappa’s Christian Gauss Award for his latest book, The Novel: An Alternative History, 1600-1800 (Bloomsbury Academic Press, 2013). Established in 1950, the Christian Gauss Award is given to books that exemplify fine literary scholarship or criticism. It honors the late Christian Gauss who served as the President of the Phi Beta Kappa Society.

Moore received his B.A. and M.A. from the University of Northern Colorado and his Ph.D. from Rutgers University. He has published numerous works, including scholarly articles, book reviews, and full-length texts. Currently, he is the preeminent scholar of William Gaddis.

The Novel: An Alternative History, 1600-1800 resumes where his previous book The Novel: An Alternative History, Beginnings to 1600 left off. In this monumental undertaking, Moore chronicles as many novels (defined as any book-length work of fiction) as he can read, wittily commenting on each and providing both historical and critical insight. He believes that the generally accepted definition of the novel is too rigid, excluding many strange and wonderful works. This book is his attempt to honor and bring to light many of these previously overlooked texts while simultaneously proposing alternative readings of more well-known ones.

INTERVIEW

What, for you, stands out as the most rewarding aspect of writing this study? And, perhaps correspondingly, what do you most want readers to take away from it?

MOORE: Until I began this study, I was a specialist in contemporary fiction. Yet I always yearned to revisit some of the older novels that I first read in college, as well as to explore premodern novels that I had heard about over the years but never had time to read. Writing this book “forced” me to go back to the very beginning of world literature (ancient Egypt and Babylon) and take a grand tour around the world of fiction, reading all the things I had never had time for and—more importantly—discovering whole new worlds of fiction. I can now say that I’ve read every significant novel published before 1800, along with many not-so-significant ones, and I take some pride in that accomplishment.

I hope that readers will come away with an enlarged view of the novel genre, of its ancient lineage and infinite variety. Most of us know only the Western classics we were assigned in college, but in my two volumes readers can learn of the literary treasures of the Middle East and Asia, of Iceland and pre-Colombian America. If, as they say, travel broadens the mind, this trip around the world of fiction should expand the mind considerably.

All together, you spent eight and a half years working on both volumes, and, in another interview, you mention that you have “overdosed on writing.” However, in addition to the time spent writing, you also had to read all the novels you discuss. Do you feel as though you have similarly overdosed on reading?

MOORE: I hate to admit it, but I do find myself taking longer to get through a novel these days, and sometimes abandon those that bore me after 30 or 40 pages (which previously I would have persevered with). I find it a little harder to concentrate for extended periods of time, but that may be merely a function of age (I’ll turn 64 later this year). Nonetheless reading remains my favorite pastime.

Given the chance, is there anything you would go back and change?

MOORE: Not really. Since publication I’ve come across the occasional old novel that I didn’t know about and now wish I had included, but nothing major. The work turned out much better (and longer) than I thought it would, so while not perfect, it’s fine by me.

For those who have not yet read the book, which of the novels would you most highly recommend?

MOORE: I’d start with Heliodorus’s An Ethiopian Romance, a 3rd-century Greek novel that is not only masterful but profoundly influential: when it was translated into modern languages during the Renaissance, it became the template for the modern Western novel. After that, Lady Murasaki’s Tale of Genji (11th century), the anonymous Icelandic novel Njal’s Saga (13th century), the pseudonymous Chinese novel The Plum in the Golden Vase (c. 1600), Don Quixote of course, another Chinese novel called The Story of the Stone (aka The Dream of Red Mansions), the great English novels of the 18th century like Tom Jones, Tristram Shandy, and The Expedition of Humphrey Clinker, and maybe the final novel I write about, Brackenridge’s Modern Chivalry (1792-1815), the first big novel in American literature.

A number of reviews for the first volume of your book mention occasional, albeit jarring, attacks on religion. Can you explain where this antipathy, if indeed it is that, comes from and why you include it?

MOORE: I wanted to make the case that novels offer a more honest view of life and a better guide to living than religious texts, so like any prosecuting attorney, that meant tearing down my opponent’s case while championing mine. Every society has two sets of scriptures: the well-known sacred ones (the Bible, the Quran, the Vedas, the Book of Mormon, etc.), and what might be called the secular scriptures of literature. Both examine the human condition and provide good and bad models of behavior, but novels, plays, and poetry are superior because (a) they are fiction and don’t pretend to be otherwise, as religious works do (and as their fundamentalist followers insist, often with deadly results); (b) novels don’t simply issue commandments but examine moral complexity: the Bible says “Thou shalt not steal,” so Victor Hugo writes Les Misérables to test that thesis by showing a man who has to steal bread for his starving sister and family. The Bible says “Thou shalt not commit adultery,” but many novelists dramatize the despair of girls who were forced into early marriages by their family and only later discover their true loves. Religious texts treat moral decisions in black and white, while novels colorize the gray areas in human interactions. Many of the early novels I treat have religious themes, or include religious characters, so I couldn’t have avoided the topic even if I wanted to, but rather than pussyfoot respectfully around the issue as many modern critics do, I decided to take the bull by the horns. Plus I’ve been an atheist since I was a teenager, and am convinced that religion (not morality: they are not synonymous terms) is a curse on mankind, the original original sin, and the sooner it is done away with, the better.

What does receiving the Christian Gauss Award mean for you and your book?

MOORE: Vindication, acknowledgement, and reward. The second volume of my novel history was pretty much ignored by the review media, which of course was very depressing. Then the Christian Gauss Award came along like a knight in shining armor to lift me up, and to verify that I hadn’t wasted my time after all. Also, the previous recipients of the award constitute a veritable who’s who of the best literary critics of the last sixty years; to be added to that noble list is a terrific honor, and since the winning book may be the last one I write, it felt like a lifetime achievement award reward for my forty-year career as a literary critic.

Adam Reece is a junior at Hendrix College majoring in English Literary Studies. Hendrix College is home to the Beta of Arkansas Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.