By Austin Harrison

Clarissa Scott Delany was born in Tuskegee, Alabama, in 1901. Her father, Emmett Jay Scott, served as secretary to the renowned Booker T. Washington while employed by the Tuskegee Institute. Washington’s presence and relationship with Emmett Scott could be deemed influential in kindling the innovative spirit who later became an inspiration to so many others.

During her adolescence, Delany was sent to New England to attend school at Bradford Academy, a Christian based institution dedicated to women’s education. Following her graduation from Bradford, she entered Wellesley College in 1919. An integrated women’s institution of higher learning was an anomaly for time, but Henry Ford Durant, who founded Wellesley in 1870, staunchly believed that diversity in race, background, and ideas was the foundation to a deeper more fruitful learning environment.

Delany grew to be celebrated for her accomplishments and contributions to campus life during her four years at Wellesley. She was an athlete on the field hockey team and became the first African-American to earn a varsity letter at the school. Delany also was a member of the debate team, a member of the Christian Association at the college, and was pledged to Delta Sigma Theta Sorority. At the Boston Literary Guild, Delany was exposed to the likes of Claude McKay and other poets, writers, and artisans of the period. Their presence and influence helped to sculpt her later writing in both content and style. These sessions would mark the beginning of her political and literary work. After graduating Phi Beta Kappa from Wellesley College in 1923, she travelled Europe, making extended stops in Germany and France.

Among the literati, Delany is best remembered as a Harlem Renaissance poet. She published four poems during her short career, beginning with “Solace” in 1925, followed by “Joy” (1926), “The Mask” (1926), and “Interim” (1927). Topics addressed in her poetry include Pan-Africanism, superstition, and the mulatto; however, she rarely spoke directly about these issues, choosing instead to rely on metaphors and allegories to convey her messages.

Delany moved to Washington, DC, after returning from Europe and taught for three years at Dunbar High School. During her time in Washington, she continued to pursue her literary and intellectual interests at fellow poet Georgia Douglas Johnson’s literary salon and the Saturday Nighters Club, a literary society for the city’s African-American intellectuals.

In 1926, Clarissa Scott married a local lawyer, Hubert T. Delany, and the two moved from DC to New York City to start their new life together. Once there, she undertook a social work project with the National Urban League and the Woman’s City Club of New York compiling statistics for A Study of Delinquent and Neglected Negro Children. The study aimed to address the incessant institutional failures of New York City, and urban environments in general, as regarding the well being of black children aged 16 years and younger.

Tragically, Clarissa Scott Delany died at only 26 years old, succumbing to kidney disease in 1927. Despite her untimely death, her work had a profound influence on the resurgence of African-Americans in the arts during the Harlem Renaissance.

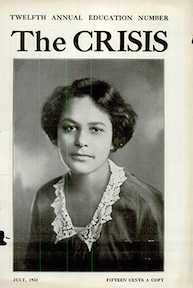

Photo: Clarissa Scott Delany on the cover of the July 1923 issue of The Crisis magazine, edited by W.E.B. Du Bois and published by the National Association for the Advancment of Colored People.

Austin P. Harrison is a junior at George Mason University majoring in environmental science with a concentration in conservation. George Mason is home to the Omicron of Virginia Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.