By Hayden Field

An African-American man wearing white medical scrubs walks alongside WSB reporter Gloria Crowe amongst the green grass of Emory University’s campus. It’s May 30, 1967, and the worry lines on his astute face speak of the hardships he’s experienced in trying to fulfill his dream of becoming an orthopedic surgeon, namely in his time with the University of Georgia.

“As I look back on it now, it wasn’t as bad as it seemed at the time, and I think certainly that if I had to do that over again that I wouldn’t hesitate,” says Hamilton “Hamp” Holmes, one of the two first African-American students to desegregate UGA.

“You have no regrets at all about going?” asks Crowe, who sits next to him on a bench.

“None at all,” he replies. “I think that I got basically a good education and good background in pre-medicine.”

Holmes’ calm demeanor and relative peace with the University of Georgia may have stemmed from years of reflection and distance from the school. He and fellow African-American student and friend Charlayne Hunter were denied admission from UGA quarter after quarter on grounds of dormitories being “full” or application procedural reasons. Holmes was asked in admissions interviews if he had ever visited a house of prostitution, a “tea parlor,” or “beatnik places.” The registrar at the time even wrote that Holmes was “evasive” and there was “some doubt as to his truthfulness” during the interview. After an almost-two-year legal battle with the University on behalf of Hunter and Holmes by members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and Atlanta attorneys, a 19-year-old Holmes registered for classes with Hunter on January 9, 1961. According to the American National Biography, they were greeted with burning crosses, a hanging black effigy named “Hamilton Holmes,” almost 1,500 spectators and a group of students shouting racial slurs and chanting, “Two, four, six, eight. We don’t want to integrate!”

On Holmes’ and Hunter’s third night at the University of Georgia, a mob consisting of about 600 students fumed for about an hour before Dean William Tate arrived, as well as Athens police, who used tear gas and fire hoses to break up the riot. The demonstration was so extensively planned that students actually brought dates to the event. It ended in injuries and arrests, Holmes and Hunter being escorted by state troopers back to Atlanta, and Dean of Students J. A. Williams notifying the two that he was withdrawing them from the University “in the interest of [their] personal safety and for the safety and welfare of more than 7,000 other students at the University of Georgia.” When over 400 faculty members signed a petition right away calling for Holmes and Hunter to be reinstated at UGA, a new court order brought the students back within a few days.

“He was amazing,” Charlayne Hunter-Gault told the New York Times about an incident in which Holmes confronted a group of racist fraternity brothers. “He had quiet dignity, scholarship. He wouldn’t let anything stand in the way of his desire to become a doctor.”

The exceedingly hostile welcome was difficult for both Holmes and Hunter. Both had graduated from Henry McNeal Turner High School, the most prestigious high school African-American students could attend due to segregation in Georgia’s public school system. Holmes was valedictorian, president of his senior class and co-captain of the football team, while Hunter graduated third in her class, edited the school paper and was crowned Miss Turner.

For the rest of his college career, Holmes kept to himself. He didn’t cultivate any close friendships at the University, instead spending his time studying, playing basketball at an all-African-American YMCA and returning to Atlanta every weekend to visit his girlfriend, friends and family. By junior year, he was “just counting the days” until graduation. He was elected to Phi Beta Kappa and Phi Kappa Phi honor societies and graduated cum laude with a Bachelor of Science degree before becoming the first African-American student admitted to Emory University School of Medicine.

The following years were full of forward-thinking and success for Holmes. He began his residency at Detroit General Hospital in 1967, left to serve as an army major in Germany two years later, and returned to complete it before becoming assistant professor of orthopedics on the Emory University faculty. He gained the title of chief of orthopedics at Veterans Administration Hospital in Atlanta, opened his own private practice, became medical director and head of orthopedic surgery at Grady Memorial Hospital and served as associate dean at Emory. Holmes stayed far away from the University of Georgia, citing his “time as a student there was very bad.”

In the early 1980s, however, Holmes was asked to help plan UGA’s bicentennial celebration and refused. He later obliged and then accept a Board of Trustees position for the University of Georgia Foundation, the school’s private fund-raising organization, of which he was the first African-American member. The 1985 celebration saw the establishment of the Holmes-Hunter Lecture, which would annually feature a significant African-American speaker to bring up current racial issues, and after the first lecture, Holmes and Hunter were given a bicentennial medallion. According to the New York Times, Holmes commended the honor by saying, “I have come to really love this university. People look at me and say, ‘You’re crazy, man. How can you love that place?’ But I will never forget this, and I will cherish it forever.”

“I would like to think I would have made it if I had not been one of the first black students here,” Holmes told the Times. “But I think I have been enriched much more because of that experience. We want to continue this with our young brothers and sisters at the university and enable them to get an education they can be proud of.”

Dr. Hamilton E. Holmes passed away in his Atlanta home on October 26, 1995, two weeks after undergoing quadruple bypass surgery. He is survived by his loving wife, Marilyn Vincent Holmes; son, Hamilton Jr., who graduated from UGA in 1990; and daughter, Allison. According to the New York Times, at the time of his death, Holmes was a staple as far as orthopedic surgery in the Atlanta community, associate dean and faculty member at the Emory University School of Medicine and chairman of Grady Memorial Hospital’s orthopedic unit. At Holmes’ funeral, Hunter-Gault spoke of their experience together desegregating the University and, in a column for the Washington Post, said Holmes was “one in a million.”

Hayden Field is a senior at the University of Georgia majoring in journalism and theatre. She’s the editor-in-chief of UGAzine, her school magazine, and hopes to one day make the world a better place by sharing its untold stories. The University of Georgia is home to the Alpha of Georgia Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.

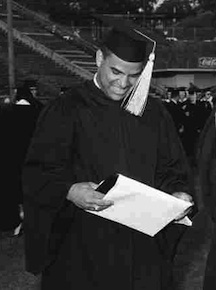

Photo at top: Hamilton E. Holmes graduates Phi Beta Kappa at the University of Georgia, 1963.