By Nicholas Dias

It is no secret that women have made groundbreaking progress in closing gender gaps – and then some – in American postsecondary institutions since the 1960s.

Popular media have by now thoroughly reported studies showing that female bachelor’s degree recipients now even outnumber their male cohorts. For example, data from the National Science Foundation (NSF) estimates that females constituted around 57 percent of bachelor’s recipients in 2012.

Ironically, articles considering gender equality among master’s recipients are much more rare, despite existing data that contend women do even better in this arena: The NSF data just cited also shows that females earned about 60 percent of master’s degrees awarded in 2012.

Yet, the truly forgotten front in the fight for postsecondary education gender equality is that over doctorates, where several studies have shown trends that are somewhat less encouraging.

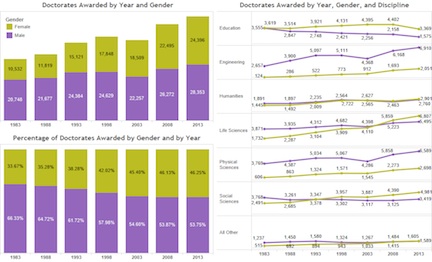

A recent post by Joe Boeckenstedt, the Associate Vice President of Enrollment Management and Marketing at DePaul University, illustrates these circumstances. One of Boeckenstedt’s visualizations of 2013 data from the National Science Foundation (NSF) is below.

To be sure, growth in the proportion of women doctorate awardees has been considerable. Between 1983 and 2013, females increased their share of awarded doctorates by over 12 percent, claiming majorities in the humanities, life sciences, and social sciences and maintaining their margin in education.

Even with these 30 years of marked progress, however, women still amounted to only 46.25 percent of total doctorate awardees in 2013.

This is because males still greatly overshadowed females among engineering and physical science doctoral graduates, constituting more than 77 and 70 percent of graduates, respectively. In fact, according to the data, the gender gap between doctorate awardees in the two fields increased by just over 40 percent from 2003 to 2013.

The damage of sociocultural elements that discourage females from entering science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields is well-documented.

One stand-out study that demonstrates these outcomes is that of Harvard University researchers Kane and Mertz. The researchers compared the Social Watch Group’s Gender Equity Index (GEI) to average math performance of fourth- and eighth-graders in 26 and 52 countries, respectively, as measured by the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS). Correlations between countries’ GEIs and average female math performances had coefficients exceeding 0.479 (p < .001).

However, shortages of women in engineering and the physical sciences may not be the only reason they continue to be underrepresented among nationwide doctoral graduates. Some states still lag far behind others with regard to gender equality in total doctoral graduates.

While states such as Vermont can boast percentages of female doctorate recipients topping 56 percent, other states like Wyoming stagnate at rates as low as 33 percent. That is a range of around 23 percent. Women receive about or above their fair share of doctoral degrees in only 16 states.

A multiple regression analysis suggests a few reasons as to why these differences exist.

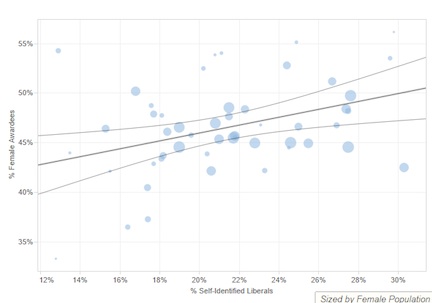

Each state’s percentage of female doctorate recipients is predicted by two other characteristics: its proportion of self-identified liberals (β = 0.68%, p < .001) and its proportion of females between the ages of 20 and 44 needing contraception (β = -0.47%, p < .05). The correlation between proportions of self-identified liberals and percentages of female doctorate recipients is visualized immediately above.

In other words, as states’ percentages of female doctorate recipients rise, (1) their proportions of self-identified liberals also rise and (2) their proportions of females needing contraception fall.

There are several apparently possible implications of these results. Pregnancy may deter women from completing a doctoral education. Areas of the country where more progressive views hold sway may elect politicians who are more inclined to support measures to bring about gender equality in education, or residents in those states may be more likely to pursue a doctoral education at a local university.

In any case, the statistics doubly underscore the import of considering sociocultural factors in discerning why gender inequality within postsecondary institutions persists in the United States.

Nicholas Dias graduated from the University of California-Davis with majors in psychology and communication and a minor in professional writing. UC Davis is home to the Kappa of California Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.