By Lisa McDonald

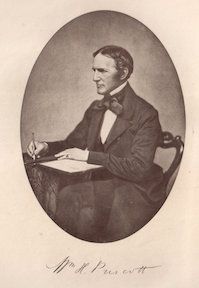

Just over two hundred years ago marks the year 1814, the year William Hickling Prescott was admitted to Phi Beta Kappa as a Harvard University senior. In present times, he is remembered as America’s first scientific historian, and his works on Spain and Mesoamerica have shaped the way both places are studied today. But what not everyone knows is the struggles he had to overcome to accomplish these writings.

Born the first child of William Prescott and Catherine Hickling, Prescott spent his early childhood in Salem, Massachusetts, before his family moved to Boston in 1808. From the start he was fascinated with literature and spent hours devouring books instead of participating in more rambunctious activities.

He attended Harvard University to become a lawyer like his esteemed father but his plan was shattered during his junior year when he was hit in the left eye with a piece of bread during a food fight. The effect was immediate, rendering the eye useless. On top of this he suffered from rheumatism causing inflammation of his one good eye, making sight only possible at small intervals or not at all.

Even if he couldn’t pursue life as a lawyer, he knew he couldn’t spend his time in purely frivolous pursuits. His dear friend George Ticknor wrote in the biography on his late friend that Prescott realized such a life “might satisfy the years of youth…but that it must leave the graver period of manhood without its appropriate interests.” So with brave determination Prescott went to work.

He set himself to reading through the English classics before moving to French literature and then to Italian. As he struggled to establish himself in German, he realized the process would take much longer than he wanted. Ticknor suggested he study Spanish instead. Here Prescott found his true calling.

In a letter written to Ticknor in January 1825, Prescott shared his excitement at having made a breakthrough in understanding Spanish: “Did you never, in learning a language, after groping about in the dark for a long while, suddenly seem to turn an angle, where the light breaks upon you all at once?”

After consideration he determined he would write histories of Spain, knowing how little there was on the subject in popular culture and that readers would be fascinated if only they knew more. But due to his poor eyesight he did not have the ability to read the resources necessary to put together his work. So he hired a college student to read to him. As he listened and took notes, he would devise and edit sixty pages at a time in his mind of what he wanted to say before making use of a noctograph—a contraption to help the blind write—to get it all jotted down.

After persevering for ten years, his first book The History of the Reign of Ferdinand and Isabella the Catholic (1837) was published. His contract with the publishing house was to produce 1,250 copies over the course of five years. When the book hit the shelves, that amount was sold in only a few months. His second book, The History of the Conquest of Mexico (1843), was produced in five years, and within five months, 5,000 copies had been sold.

Before his death in 1859 he produced three more major works with each succeeding doing even better for sales. But for Prescott, it was never about the money. Prescott wrote for himself and the expansion of public knowledge, and he made sure to do it in a way that was solely his own. Before beginning Ferdinand and Isabella, he said “every one pours out his thoughts best in a style suited to his own peculiar habits of thinking,” a statement he held close to his heart for his entire writing career.

Though he was awarded countless honors and awards (many he didn’t even campaign for) what he liked most was the ability it gave him to help others. Prescott served as a trustee for the Perkins School for the Blind and wrote articles educating people on the necessity for such institutions, succeeding in raising $50,000 for the school. In his private life whenever he heard of people in the community who needed help, he never failed to send a friend to deliver money or supplies to make sure the people would not suffer.

This was all accomplished by a man who could barely see and sometimes not even walk. When Prescott was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa all those years ago in 1814, he didn’t know what his life would become. But he did know that being invited to join was one of the greatest honors he ever did receive, and he always strived to uphold the title of such an honorable society. In the two hundred years since his admittance into the society, it is not hard to see he was able to do just that.

Lisa McDonald is a sophomore at Coe College majoring in Physics and Communication Studies. Coe College is home to the Epsilon of Iowa Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.