By Joe Slama

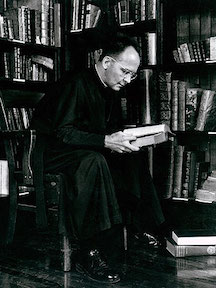

It is a rare humanities scholar who fundamentally shifts our understanding of humanity itself. It is an even greater distinction within the Catholic church, an institution that has had its cosmologies and anthropologies set by a small number of its widely revered scholastic saints. The last century, however, saw one such scholar in Walter Ong, S.J., an honorary inductee of ΦΒΚ in 1967 at St. Louis University.

Ong was a bulwark of liberal studies in his day and is still fondly remembered in circles within the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) as well as in anthropology and literary studies.

His name resurfaced recently on the campus of his home institution, when SLU erected a marker in his honor. The sign was the premier in a series “Pillars of the University,” which aims to honor great scholars of the institution during its bicentennial celebrations. SLU was founded as a Latin school for boys in a one-room schoolhouse on November 16, 1818.

It is uncannily fitting that Ong would be the first in a series of figures to be commemorated prominently in writing on his former campus, as he was one of the founding scholars in a unique movement to study the written word during his long tenure at the university.

Walter Ong graduated from Rockhurst High School in Kansas City in 1929 before receiving his Bachelor’s in Latin from Rockhurst College in 1933. He entered the Jesuits in 1935 and was ordained a priest in 1946. He earned his Master’s in English in 1941 while still in formation for priestly ordination, and in 1955 earned his Ph.D. at Harvard. He also earned Licentiates in philosophy and theology at SLU. He passed away in 2003 in St. Louis.

Over the course of his academic career, Ong published over 450 written works, including academic writing as well as poetry. He served on the National Council on the Humanities, White House Task Force on Education, National Commission on the Humanities, and Modern Language Association (President, 1978), among other famous names. He was also a Phi Beta Kappa Visiting Scholar from 1969 to 1970. SLU granted him the school’s highest honor, the Sword of Ignatius Loyola, in 1993.

According to the university’s profile of this late scholar, Ong once explained his graduate work in English thus: “English seemed intellectually and culturally roomier and more open than other subjects. It could encompass what they did and more—could open the way into almost anything.” This was an apt description for a man with such depth and breadth to his prodigious intellectual arc.

Ong built credentials in a variety of fields to a degree unusual for even a Jesuit. He was a literary critic, cultural commentator (America Magazine, the national publication of the Jesuits in the States, recently re-published Ong’s skeptical piece on Mickey Mouse), and religion scholar.

However, his primary interests lay deeper within the realm of literature, in the words themselves. He is best remembered for his investigations into the fundamental differences between literate cultures and oral cultures (where the written word has not developed or is not widespread). He published four cornerstone works on the subject, culminating in Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word (1982).

Ong’s work on the written versus spoken word had enormous ramifications for the understanding of human psychology. His work was based primarily in Homer’s epics and Greek philosophy in a contrasting pre- and post-literate society, but has implications for the universal understanding of human consciousness and thought.

Ong observed that the availability of external information storage — that is, the written and preserved word — drastically changes a society on levels linguistic, cognitive, and social. Oral cultures, for example, speak in simpler (“additive”) sentence structures, where literate cultures produce more grammatically complex (“agglutinative”) sentences by subordinating elements. Only literate cultures are capable of lists and tables. Oral societies value one’s stance within a community; literate cultures prize individualism. Cultures that rely on the spoken word are suspicious of change and adhere to the past in their oral traditions; literacy allows societies to store information about the past, and thus encourages innovation. Literate cultures tend to become widely learned; the vast majority of languages are only ever spoken aloud, existing in oral societies, and thus are never recorded onto a page. These are merely a few of the many contributions that originated from Ong’s work.

Ong’s career spanned a transitory period in human history: he died in 2003, less than a quarter of a century after the invention of the internet. He also took an interest in the growing impact of electronic and digital media (and, naturally, published on it as well), a form which has impacted in some degree anyone reading this article. He appears almost as a prophet, one who read the signs of the past that had transformed human consciousness even as yet another information revolution similar to the invention of orthography was underway.

Ong scholarship is ongoing as his work continues to be unpacked (it even gained a name among his SLU students: “Onglish,” because of the variety of fields in which the priest was fluent). His achievement stands as a proud beacon for the use of liberal studies: Ong was a humanist in the truest sense, wielding all manner and kinds of knowledge to unlock the deeper secrets of humanity.

Joe Slama, a senior at Truman State University studying Classics, was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa in spring 2017 while studying and working in Rome. Truman is home to the Delta of Missouri chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.