By Alexis Sargent

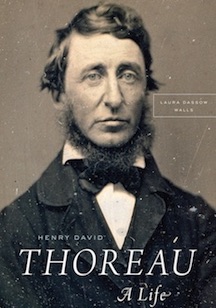

Henry David Thoreau: A Life by Laura Dassow Walls is the recipient of Phi Beta Kappa’s 2018 Christian Gauss Award. Established in 1950 to recognize outstanding books in the field of literary scholarship or criticism, the award honors the late Christian Gauss, the distinguished Princeton University scholar, teacher, and dean who also served as President of The Phi Beta Kappa Society.

The William P. and Hazel B. White Professor of English at the University of Notre Dame, Walls is the author of numerous works related to Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, American Transcendentalism, and 19th century science. Her scholarship has been supported by the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Council of Learned Societies, the Center for Humans and Nature, and the William P. and Hazel B. White Foundation.

Walls’ publications include Seeing New Worlds: Henry David Thoreau and Nineteenth-Century Natural Science (1995), Emerson’s Life in Science: The Culture of Truth (2003), and a work coedited with Joel Myerson and Sandra Harbert Petrulionis, The Oxford Handbook of Transcendentalism (2010). Walls’ The Passage to Cosmos: Alexander von Humboldt and the Shaping of America (2011) also earned several awards, including the Merle Curti Award for intellectual history from the Organization of American Historians, the James Russell Lowell Prize for literary studies from the Modern Language Association, and the Kendrick Prize for literature and science from the Society for Literature, Science, and the Arts.

In Henry David Thoreau: A Life, Walls not only focuses on Thoreau’s passion for nature and his publication of Walden in 1854, but also traces the full arc of Thoreau’s life in all its complexity. Starting with Thoreau’s early years in the intellectual community of Concord, Massachusetts, Walls presents a complex, alive Thoreau whose experiences deeply affected the development of his character, experiences such as the death of his brother, his time as a Harvard College student, his work as an avid abolitionist, the admiration he felt for his mother and two sisters, and his emergence as an individual who found solitude and solace in nature.

As a Transcendentalist Thoreau advocated the philosophy of living, Walls explains, “so as to perceive and weigh the moral consequences of our choices.” Environmentalism and social justice, the importance of individual integrity as well as devotion to the community and the common good—many of the great questions and dilemmas that drove Thoreau persist for us today, and we continue to look to him for inspiration.

INTERVIEW

Your new biography has been praised by other Thoreau scholars as meticulous and revealing. A review in The Guardian described it as radical and unsettling. What can readers look forward to learning in Henry David Thoreau: A Life that they might not have known before?

WALLS: It came as a surprise even to me to learn how early Thoreau engaged in social causes of various kinds. I’d always understood he hung back until long after his mother, sisters, and aunts had paved the way, coming in to give his public anti-slavery addresses rather late, and reluctantly. It’s absolutely true that the women in his family took the lead here, but as women, they were unable to speak in public themselves or make certain business arrangements for speakers and publications. Thoreau stepped in pretty early as a kind of silent partner, and the more he helped, the more radicalized and passionate he became; by 1859, he was leading the whole town in an act of civil disobedience! This really got underway in 1843, after he returned from living on Staten Island to discover his household was a center of abolitionist agitation. By then he was ready to listen, for his own experience in New York City had begun to radicalize him. That was another surprise to me—the role his months away in Staten Island played in his life. Before that, he was an Emerson apprentice; after that, he was his own person, quite rebellious, on a path that took him straight to Walden Pond. Finally, the big surprise was to discover how social Thoreau actually was. Not that he was often the life of the party (although he did throw annual melon parties!), but that he led a life rich with friends and family, who genuinely enjoyed his company and whom he loved deeply in return. And he mellowed greatly over the years, too, especially after Walden established his reputation as a respected American author, not just the town crank. Yes, the prickliness was there too, for he could be quite cutting when he thought he detected shallowness and hypocrisy, and he fiercely protected his solitude. Thoreau was not above using rudeness as a shield when he was on a writing jag, which was pretty often.

Thoreau was a social activist during a pivotal time in American history. However, he is more commonly remembered as a nature writer. Has our perception of him been overly selective?

WALLS: I think it has, although there has always been a strong interest in his political writings; in fact, Thoreau’s reputation as a great writer began in the late 1800s when a group of British Socialists discovered Thoreau and started to celebrate him as a great writer—not just a great nature writer, which was the reputation he’d had until then. These British fans were astonished to find that so few people in the U.S. recognized Thoreau’s greatness, and they set about correcting this omission. In part this disparity—focusing on the nature writing, while overlooking the political writing—is due to the Transcendentalists themselves, who tended to dismiss their own social and political writings as too temporary and topical to have permanent value. I think Thoreau himself thought of “Civil Disobedience” as an occasional piece, like his anti-slavery addresses; he certainly didn’t prioritize it. But the other aspect of this is that to Thoreau, nature writing WAS political, profoundly so, and he addressed it as such. That’s very, very clear in the opening of Walden, for instance. He would be immensely disappointed at how we unconsciously separate the two. To Thoreau, Nature was the most radical reformer of all.

Your multifaceted view of Thoreau includes not only the details of his life and significant relationships, such as with Emerson, but you also focus on Walden in particular. What special role does this book have in your approach as a biographer?

WALLS: As a literary work, Walden deserves, and has frequently received, its own treatment—which often stretches to book length all by itself. As a biographer, I was torn: How could I not talk about Walden, the book? Yet when I tried, the narrative movement came to a full stop as I fell back into my “professor” voice. I was lecturing on stage instead of stage managing invisibly from behind the scenes. So I cut most of that, keeping the actual discussion of Walden as short as I could manage; but I made Walden—that is, the place, the concept, the ideal, the experience, the way writing it made Thoreau into a real writer—into the center and climax of Thoreau’s life. Thus Walden is, in some sense, on every page of the biography. Thoreau’s two years, two months, and two days at Walden Pond made him who he was, and he knew it; the experience of writing Walden, of becoming the kind of person who COULD write Walden, took nine years of his life. The year after he published it, Thoreau became deathly ill with tuberculosis, and I’m sure he thought that was the end. When he recovered, his next move was not to linger on the past, but to reinvent himself. That’s when he returned to Maine, for instance, and began both his late, great natural history essays and his ecological science studies. I feared these years would be too anticlimactic—after Walden, who cares?—but in fact, I found those years tremendously exciting, as he begins his ascent to a whole new and larger vision. Most of this, though, was unpublished, since he died too soon. Tuberculosis only gave him another five years before it returned and stole his life away.

In your book, you discuss how Thoreau has become “the iconic hermit of American lore.” Can you comment further about his status as an American icon?

WALLS: As an American icon, Thoreau stands for many things for many people—whether they’ve read him or not. For lots of people he stands for something they love, or hate: saint or misfit, far-sighted social visionary and political resister or selfish, cranky curmudgeon. The “hermit” icon crystallized around Thoreau while he was living at Walden. After all, he was quite the curiosity, out there cultivating his beans, living in that absurdly tiny house on the road out of town, and the easiest way people could process what his experiment was all about was to call him a hermit. He wasn’t, really—there was a town hermit, out in the woods on the Concord town boundary, and one time Thoreau tried to visit him. But the hermit wouldn’t come out and talk. That’s the point!—that’s what a real hermit does. By contrast, Thoreau for most of his life lived in a big busy household and talked to everyone. He’d talk your ear off, if he had a mind to. He lectured, he wrote incessantly, he published, he kept up a sizable correspondence (writing letters every week), he ran off to hang out with friends nearby, sometimes for weeks on end. And all the time he was making his living by surveying, which meant associating daily with all kinds of people. But we hold onto the “hermit” icon nevertheless, because there’s tremendous appeal to the purity of the ideal, an appeal that drew Thoreau as well—it became his performative stance, as a writer. But there’s an interesting kick-back to that: we also distrust the loners, the solitaries. They are acting out a rejection of our society, of us, and that stings. We feel insulted. The classic way to lash out is to accuse Thoreau of hypocrisy, for not being a pure hermit, for not being what he never claimed to be in the first place! That’s the danger with becoming an icon: you’re frozen in amber.

Transcendentalism appears to have had its day, but Thoreau has remained a touchstone for those seeking to “live deliberately”. How is Thoreau particularly relevant for our times?

WALLS: If I had a dollar for everyone who told me we need Thoreau now more than ever, I could afford a first edition of Walden. Transcendentalism was a social and religious reform movement, and while it left many traces on our life and culture, and while the actual Transcendentalists were a lively and fascinating group of eccentrics, for the most part, their writings interest only historians. It’s the really great writers—Emerson, Thoreau, Fuller, Louisa May Alcott—who live on for us, whose words capture us still. Thoreau is, to my mind, the best of them all, for he discovers how to embody philosophical abstractions in living, pulsing reality. His “nature writing” is really metaphysical writing, enacting the great, tough questions about the nature of life, whether it’s mean and nasty, or glorious and sublime—not as some academic debate, but lived actions, commitments written in body and bone, sensual immersion in the world. As long as we have bodies, and as long as we have some sort of wild world around us—even if just a few mice and weeds to annoy us!—we’ll have enough to connect with Thoreau. As for us today, the great questions that drove him—how can I retain my individual integrity in a conformist society? How can I live a decent, honorable, ethical life when the way we live means committing acts of injustice to others?—are more pressing than ever. I’ve often been asked what Thoreau would say or do about one or another of our relentless series of crises. It’s impossible to say for sure; he’d have his own opinion, but alas, he’s really not here to share it with us. What he might say is: First, connect to the core of your being, what holds you together as a person. Then, ask how that core connects to all that holds us together as a community—and your answer must, absolutely must, embrace all members of that community, the weak and the vulnerable above all, right down to those mice and weeds. Only then can you claim to be living something close to an ethical life. We are all of us each other’s neighbors, each other’s environment—that’s the message of Walden. Once you get that straight in your head, you’ll know what to do.

As a Phi Beta Kappa member, is there special significance to you in winning the Society’s Christian Gauss Award?

WALLS: There certainly is. My mother was very proud of having earned her ΦBK membership back in the 1950s, as a returning student with a family to raise while working as a writer and editor. (My father, a scientist, was equally proud of his Sigma Xi membership.) For them, recognition by these honorary societies meant they had indeed realized their dream: both my parents grew up in poverty, and they ran away together to Seattle, the “Big City,” to attend the University of Washington and make a better life for themselves and their children. When I earned my ΦBK membership, my mother insisted on giving me the fanciest gold key and sat with me proudly at the induction ceremony. We always had copies of The Key Reporter and The American Scholar around the house, and as a precocious kid I enjoyed reading them because, unlike my school textbooks, in their pages ideas of all kinds seemed to come alive. I was reading about the Christian Gauss Award winners before I ever knew that I’d go on to write books myself—so this award loops back all the way to my earliest childhood dreams, and before that, to the faith my parents had in public education.

Alexis Sargent is a senior at Michigan State University studying social and public policy. She was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa in spring 2018, during her junior year. Michigan State University is home to the Epsilon of Michigan chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.