By Beks Freeman

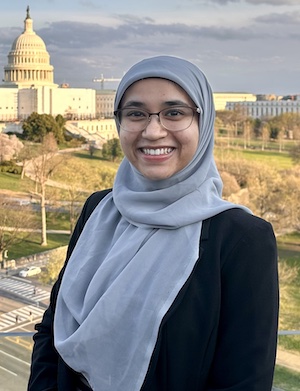

Samiha Islam, a junior majoring in Health & Human Services and Statistics at the University at Buffalo, received a Key into Public Service Scholarship from Phi Beta Kappa in 2022. She continues making strides in the world, turning her skills in art and statistics toward activism and celebration.

Inspired by many Phi Beta Kappa members who have shaped the course of our nation through local, state, and federal service, the Society’s undergraduate scholarship highlights specific pathways for arts and sciences graduates to launch public sector careers.

Islam combines mixed media art journals with statistics and data analysis to fight xenophobia, Islamophobia, and oppression. “I’ve been making various forms of art ever since I was little, but the statistics aspect is a more recent development,” she said. A year ago, Islam added a second major in Statistics to her primary major in Health & Human Services to bolster the qualitative research she does as part of her social justice work, which focuses on students of color, migrants, and those who live in poverty in her hometown of Rochester, New York. The University at Buffalo’s UBNow recently featured Islam’s unique style of journaling in a story about her and her work as a diversity advocate in UB’s Intercultural and Diversity Center.

Combining the arts with science gives Islam a fuller picture of how systems impact marginalized communities — a picture that individual experiences or statistics do not fully show on their own. “Systems are embedded in intersecting institutions — like schools, hospitals, housing, and neighborhoods,” Islam explained. This framework shifts blame away from systemic oppression, blaming instead individuals and their choices for the system’s negative socioeconomic outcomes. “You can’t argue with numbers, though,” she said. “Data isolates variables that point to one’s experience with racism.”

Islam’s artistic side helps her embed empathy into the data, recognizing people’s complexity. “Algorithms are so often weaponized against people of color,” she observed. “Predictive police algorithms increase arrests in Black neighborhood . . . and standardized testing data has racist implications.” Islam uses data as proof of systemic inequalities while acknowledging that data does not tell the full story. To avoid reproducing systemic oppression, Islam said: “The solutions still have to be defined by the community itself, as the experts of their own experience. That’s where my empathetic, artistic side comes into conversation with my study of statistics.”

Even Islam’s art is true to her mission to uplift diversity. She practices a form of traditional journaling combined with visual art to process her own experiences and inspire those around her. The pages of her journals balance pain with joy, containing reflections on Islam’s relationships with others and the uncomfortable conversations that she must navigate in the field of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. Her unique and highly personal art allows her to “process the grief of daily injustice, but also express the joy that comes from serving people I love,” she said.

That balance of holding space for trauma and joy together is important to her advocacy. Islam explained that she learned from community organizing that we should not stand against problems as much as for solutions. “By only defining yourself as the antithesis of your oppression, you burn out,” she said. “Liberation is more than what we stand against; it is a reality where we can live authentically.” Islam acknowledges the tragedy in the experiences of marginalized people but focuses on celebrations of their resilience, creativity, and culture. She titled a page in her journal “They Hated Us, so We Learned To Love Ourselves,” which she said is a fitting encapsulation of her mission. “That embodies how I choose to keep hope,” she said, “immersing myself in spaces that cultivate love for the refugees, immigrants, students of color, and people I serve.”

“The work of accountability is both an internal and external process,” Islam noted. For example, while legislators and elected officials are responsible for providing tangible, systemic responses to social justice issues, other kinds of change can happen on a personal level. She’s seen how the Tough Topics conversations she has hosted through UB’s Intercultural and Diversity Center go beyond the room. “Students take those conversations to their classrooms, sports teams, dinner tables, and houses of worship . . . in a way that balances compassion with accountability so that we don’t perpetuate harmful power dynamics in the process,” Islam said.

One might think tension in conversations would be discouraging, but Islam sees hope in the conflict. She finds inspiration when a conversation gets tense, but the relationship holds. “It’s not realistic to assume we can change someone’s mind; people must choose to do that for themselves,” she said. “But we can maintain a relationship of trust, compassion, and accountability while working to desegregate our ways of thinking.” Despite the exhaustion that can come from doing this hard, careful work, Islam also draws inspiration from how her peers persist. “It’s what makes me believe that equity is possible in the long term.”

“I firmly believe that you do not have to be a conventional type of leader to make change,” Islam said. Her favorite part of advocacy work comes from human connection, where everyone can lead: “You hold power in the things you choose to pay attention to, who you include in your conversations and friend groups, how kind you choose to be, and how you react to situations of injustice. You can always use the power you have access to. It starts with identifying what communities you already inhabit.”

Her interdisciplinary approach to service is gaining further attention. Samiha Islam became UB’s second Harry S. Truman Scholar on April 14. She will use the scholarship, she explained to UBNow, to “pursue an MS in data analytics and public policy to holistically address resource inequality in racially segregated cities, ultimately improving social service coordination between nonprofit groups across the Northeast.”

Beks Freeman (they/he) is a senior at Purdue University double majoring in acting and creative writing. They were inducted into Phi Beta Kappa there in April 2022. Purdue University is home to the Zeta of Indiana chapter of Phi Beta Kappa. In addition to their undergraduate studies, Beks is pursuing acting, teaching, and fight directing certifications in stage combat with Dueling Arts International.