By Colin Rafferty

The Cold War, and the massive arms buildup that drove it, required both a remarkable amount of plutonium for nuclear weapons as well as layers upon layers of secrecy, both from foreign spies and domestic citizens. The single facility producing “buttons”—small discs of plutonium used as triggers for nuclear weapons—was Rocky Flats, a beyond-top-secret site approximately a half-hour drive from Denver, Colorado, but even closer to the small town of Arvada, where author Kristen Iversen grew up, eventually raising a family on her own nearby.

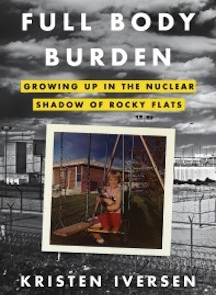

The story of Iversen’s family and the story of Rocky Flats—its founding, its mismanagement, its accidents, its raid by the FBI (the first time one government agency raided another) and its eventual shutdown—are the parallel narratives of Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Nuclear Shadow of Rocky Flats, a book that masterfully combines a coming-of-age narrative with investigative journalism.

Iversen’s book is not an objective work of journalism; instead, it’s partially a memoir about the experience of growing up near one of the most secret—and, eventually, one of the most poisoned—places in the world. When the plant was announced, the Atomic Energy Commission told residents that Rocky Flats would produce nothing connected to nuclear weapons. Despite the objections of at least one engineer, the plant was constructed upwind of Denver, a small city that would grow into a large one over the next few decades. Accidents and releases of radioactive materials were passed off as harmless to employees and the surrounding communities. The United States government shrouded the plant in absolute secrecy, but as news of accidents and mishandling of fissile material slowly leaked out of the plant, a protest movement arose, made up of everyone from former hippies to Catholic nuns.

This is the background in which Iversen and her siblings came of age. She describes pony rides along the plant’s fence and dates with local boys. She works as a waitress, and on a Ph.D at the nearby university, and even, for a time, works as a temporary employee inside the plant itself. Through the book, she observes and deals with her parents’ marriage, a relationship that seems as mutually destructive as the global arms race taking place at the same time. Her characters are treated respectfully but honestly, and she builds each one into a fully-recognized human, capable of joy and sorrow, affected by happiness and tragedy—even if disaster follows them the way that it seems to follow the plant.

But to think of Full Body Burden as a memoir, even a well-written, engaging memoir about a family’s collapse, is to see only half of the book. Iversen neatly sidesteps the memoir’s potential pitfall of solipsism by carefully researching the history of the plant, tracking down and interviewing former employees and whistleblowers, as well the surviving family members of people sickened by exposure to radioactive materials. She writes the experiences of these people as vibrant, alive scenes, capable of great sorrow, as in the case of those made sick, and of great terror, as in the case of those fighting catastrophic fires at Rocky Flats. She describes the plant’s “infinity rooms,” spaces so contaminated by radiation that they have been sealed off, never to be opened again. Often, the book is a frightening exploration of America’s nuclear history, cataloging the times we skirted the edge of nuclear disaster—and the times we stepped right over that edge.

Full Body Burden is a necessary read, a lamp shone into a disastrous and little-discussed corner of American history. In our mad race to beat the Soviets in nuclear weaponry, we made our land toxic, not caring what—and who, in the case of Iversen’s family and hundreds of others—became collateral damage, made, in the words of the nuclear industry, “hot” in pursuit of winning the Cold War.

Colin Rafferty (ΦBK, Kansas State University, 1998) teaches nonfiction writing at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Mary Washington is home to the Kappa of Virginia chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.