By David Madden

“From the heart … and the pen of

LILLIAN HELLMAN,

celebrated author of

“The Little Foxes”

comes another unforgettable masterpiece,

“WATCH ON THE RHINE”

set to the soaring music of Max Steiner, showed up on the screen of the Bijou in Knoxville, Tennessee when I was ten years old. The name LILLIAN HELLMAN, along with such names as ERNEST HEMINGWAY and JAMES M. CAIN, all caps as if on marquees, inspired me, always more influenced by movies than books, to become a writer at age eleven.

I remained under the spell of her name as I read all her plays by age thirteen, especially THE CHILDREN’S HOUR (indulge, please, all caps), and read or saw all the plays thereafter and reviewed her trio of memoirs. Her beaky profile, enhanced by her upswept hair-do, especially set beside the profile of her lover, tough guy writer, silver-haired Dashiell Hammett, was for me iconic. What she has been for me, she has been for many others, at least until recent years.

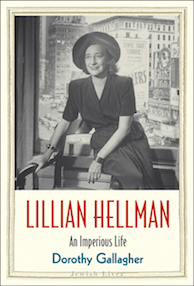

Little wonder that I turned with high expectations to Dorothy Gallagher’s biography, LILLIAN HELLMAN: AN IMPERIOUS LIFE (dropping all caps hereafter). The adjective “imperious” struck me as just right, but Gallagher did not mean what I had always meant. The task she sets for her self is to dismantle an empress. I don’t mind. As she admits, Hellman’s plays are monumental, the best being the work of a young woman who reigned for twenty years as the only woman playwright of great consequence—the queen of Broadway playwrights.

Within the scope of a mere 141 pages of text, Gallagher tells the basic, known Hellman story, including the stand-out Hellman-Hammett story, making choices that will likely strike many readers as very odd. She expends twenty-seven of those pages in two digressions as puzzling though not as illuminating as Melville’s “Whiteness of the Whale” and “The Cetology of the Whale” in Moby-Dick. “The Hubbards of Bowden” and “The Marxes of Demopolis,” chapters one and two, reveal Gallagher’s passionate interest more in the two sides of Hellman’s family than in Lillian herself. Those chapters are interesting in themselves, appropriately so, because this book comes out of a series called “Jewish Lives.”

More in the spirit of gratuitous digressions is the third chapter, “Two Jewish Girls,” in which Gallagher draws parallels between the ancestry and early lives of Hellman and Gertrude Stein. Yes, interesting, but readers in the margin will ask, “When do we focus on Lillian Hellman?” The answer is in the next chapter, which is about her first marriage, and her legendary romance with Dashiell Hammett. He remains far more famous today than Hellman, whose life and work is fading from the national consciousness. The title of the next chapter, “The Writing Life: 1933-1984,” promises more than it delivers, the focus remaining on Hammett’s role in Hellman’s writing, during a time when Hammett the alcoholic wrote very little. Gallagher gives the impression that although her plays and screenplays dealt boldly with contemporary issues, her writing life was not really a life of the mind. She posed issues dramatically; she did not delve deeply into them.

What I have written so far may seem to be finding fault, but it is more descriptive than critical. Gallagher, author of four previous books and many articles, writes uncommonly well, in a kind of tough voice like Hellman’s, and like her arch-enemy Mary McCarthy, who famously accused Hellman of lying in her memoirs (Gallagher tells that story well too). She brings her lovers, her friends, her enemies, her travels, especially to Russia, and her fixation upon money into play, reminding readers that Hellman rather recklessly, but, as a communist sympathizer, courageously defied the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

Generally, Gallagher seems to join satirical novelist Mary McCarthy in severely questioning Hellman’s self-cultivated “reputation as a woman of moral courage, honesty, and integrity.” Some readers will balk, but many are likely to find Gallagher’s somewhat unique way of writing about a life very enjoyable, if not particularly illuminating.

David Madden (ΦBK, University of Tennessee, 1979) is a novelist and resident member of the Epsilon of Tennessee chapter of Phi Beta Kappa. Madden’s fourth book of stories, The Last Bizarre Tale, comes out in August.