By Louis J. Kern

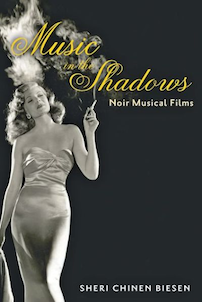

Extending Rick Altman’s argument that musicals reflect the “convergent nature of many genres commingling and cross-pollinating,” Biesen contends that traditional musical films were diegetically, tonally, and aesthetically darkened through the incorporation of noir cinematic technique—lighting, camera angles, mise-en-scene—psychology, and sensibility to create a hybrid form she calls the “noir musical.” She considers the prototypical Blues in the Night (1941), the more definitively noir Gilda (1946), and a succession of classic post-war films (1945-54) that established a convention of shadowy criminality, erotic violence, seductively menacing women and damaged men overwhelmed by a morally ambiguous, nightmarish subcultural world of the nightclub or seedy roadhouse.

Grounded in substantial archival research, Biesen extends her consideration to films she describes as “dark musical melodrama” such as Love Me or Leave Me (1955) and West Side Story (1961) and such neo-noir films, awkwardly denominated “postclassical dark neo-noir musicals” as Cabaret (1972), Pennies From Heaven (1981), and Moulin Rouge (2001). Providing a challenge to conventional genre criticism, the volume delineates the broadly inter-genre and inter-mediated nature of these films, incorporating dramatic elements of mystery, suspense, romance, and crime in the context of dance and music.

Biesen also explores the cultural context—acclimatization to violence and changing sex roles in the wake of WWII, nascent civil rights agitation, Cold War paranoia, and post-Vietnam disillusionment—as well as technical and production issues—the transition from black and white to color film and from nitrate to cellulose filmstock, and the tortuous history of film censorship. But a more rigorous exploration of inter-media connections is needed, especially those associated with such a closely related sequential art as comics. The legacy of noir is clearly present in such contemporary examples as Frank Miller’s successful black and white graphic novel series Sin City, currently experiencing its cinematic sequel as Sin City: A Dame to Die For, and Jules Feiffer’s new graphic novel Kill My Mother, set in James M. Cain’s Bay City. The censorship restrictions of comics might quite fruitfully be compared to those of contemporary cinema.

At times Biesen’s argument is stretched thin—one or two songs in a noir style film is sufficient to classify it as a “dark,” musical, e.g., Casablanca (1942) and The Big Sleep (1946). Jazz documentaries like Jammin’ the Blues (1944) are neither noir nor genre musical. And it is difficult to credit the bright, classical Busby Berkeley spectaculars as “preludes” to musical noir. A more serious problem is a curious tonal deafness. Discussing The Wizard of Oz she cites the “stark black and white” of the prologue, when it is actually in sepia tone. It is intended not to convey an ominous Kansas but rather a nostalgic, romanticized past. The noir connection to Dennis Potter’s BBC t.v. series Pennies From Heaven (1978) is even more tenuous. While admitting that it has been called an “anti musical,” Biesen overlooks its post-modernist pastiche and parodic nature. Unlike the American version, it is a conscious inversion of the uplifting romantic Bing Crosby vehicle of the same title from 1936. It cynically cannibalizes the popular hits of the 1940s and parodies the conventions of the classical musical by halting the dramatic action for songs that are lip-synched (often with gender inversion) with totally jarring effect, savagely intensifying the hopelessness of the protagonists.

Despite its shortcomings, Music in the Shadows is an interesting and provocative approach to post-genre film criticism that underscores the interconnectedness of diverse media, and provides both a challenging perspective on the musical genre and a testimonial to the ongoing legacy of noir sensibility.

Louis J. Kern (ΦBK, Clark University, 1965) is professor emeritus of history at Hofstra University. Hofstra University is home to the Omega of New York Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.