By Lewis Fried

Nicholas Basbanes is something of a national treasure, bringing what is often called “book culture” in front of us. In an age of the digital page, when books can be downloaded, when e-mail and twitter are developing a distinctive lexicon and rhetoric, when the book itself seems to be on its way out of our private and public culture, Basbanes returns us, again and again, to the importance of paper, as we knew it, know it, and, hopefully, shall maintain it.

On Paper celebrates that “ubiquitous” commodity, and its manifold uses. This book is characteristically engaging and authoritative, as Basbanes explores paper’s role and manifestations, preserving the expression of mind. As he makes clear, one of its achievements is to a repository for memory and endeavor, an archive of the human spirit. As a surface that can receive and hold a variety of markings—from ink to oil—it ingathers all things effable. Paper is perhaps the best presentation of our mind that we have and invariably collect, catalogue, and in our mundane, and casual daily life, throw away.

It is also a medium in which form and function can rarely be pulled apart. Whoever has touched artisanal paper, or skimmed a finger across the sheets of chain-lined paper, or experienced the visual delight of seeing raven-black printing on rag paper cultivates a pleasure that is vanishing from our present day. As a result, paper attracts us both to art and an art form. Our cheap pulp paper, disintegrating, yellowing, and becoming brittle, roots us, so often, in a civilization that makes reading accessible and democratic, but delivers us to a text that survives without a grand acknowledgement of the importance of seeing, touching, and holding. Of course, we read and treasure a book for its author’s imagination and exposition, but we honor paper for its making these possible. And, in the case of hand-crafted paper, for its presentation.

On Paper is, in part, an historical mapping of the spread of paper; wherever it went, so, too, did it carry our transactions, in the largest sense possible. From contracts and letters, to art and meditation, its functions seem inexhaustible and ever-present. The Chinese claim it as theirs: “one of their four outstanding inventions of antiquity.” In the aftermath of 9/11, paper became a medium preserving the memories of those killed in Manhattan, as well as a means of keeping alive a dialogue with them.

However, Basbanes is not writing a book confined to the geography of paper. Among the pleasures of reading On Paper is Basbanes’ search for paper’s various manifestations, their means of production, uses, and consequences. Such an embracing approach is helped (and in some cases diminished) by On Paper’s tangents. Depending on your expectations, the book either addresses what its subtitle states—The Everything of its Two-Thousand-Year History—or carries along the reader in Basbanes’ expositions and examples of unexpected, and surprising subjects. For examples: toilet paper? Yes, it is included. The Sepoy Mutiny? Yes, also discussed and well-presented, with attention paid to the Enfield’s barrel and the use of animal fat (pig and cow) in cartridges, fats “repugnant” to Hindu and Moslem.

I think one of the grand virtues of the book is Basbanes’ portraits of those who make artisanal paper—hand-produced, and done with an eye and feel for texture. We are taken into workshops where we meet papermakers who discuss what brought them to this work. In contrast, we are brought into large mills in which the market drives demand and diversity.

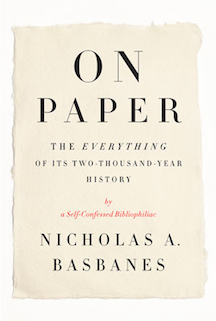

The book itself combines these aspects—hand-worked and commercially manufactured paper. Textured paper is pasted on the front cover, and commercially made paper is used for the text. Although I cannot find a reference to the maker of the front cover’s pasted paper (though the jacket design is by Jason Booher, and the book design is by Cassandra Pappas), it brings to sight and touch what pleasures paper presents. And, what pleasures On Paper contains.

Lewis Fried (ΦBK, Queen’s College, CUNY, 1964) is Professor of English Emeritus at Kent State University and a resident member of the Nu of Ohio chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.