By Indira Ganesan

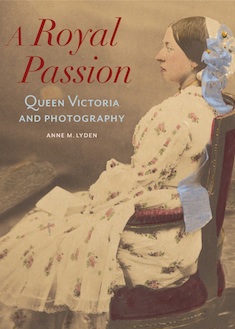

A coffee table book must do two things well: provide interesting commentary and a wealth of pictures. Anne M. Lyden’s book, A Royal Passion: Queen Victoria and Photography, does just that. Issued as an accompaniment to the Getty Museum’s 2014 spring exhibit curated by Lyden, this slim, heavy volume is composed of one-third text and two-thirds photographic plates and photos depicting both royal and non-royal subjects. The opening essay by Jennifer Greene Lewis looks at the history of photography, invented by Louis Daguerre almost two years after Queen Victoria took the throne in England. She describes the colorful race to acquire and refine the medium by two English scientists, Sir John Hershel and William Talbot, the efforts of Talbot’s mother, Lady Elisabeth Fielding, to publicize and promote his “photogenic specimens” and get them to Buckingham Palace, as well as the influences of photography on the Pre-Raphaelite painters. George Eliot and Thomas Hardy were not unaware of the long view the photograph could provide, and Lewis describes “an increased imaginative sympathy for the lives of the working poor, and to force a growing sense of the commonality of human existence.”

Victoria’s interest in the new medium was considerable. She lived for eighty-one years, and ruled England for sixty-three years. Throughout her reign, she sat for numerous official and family portraits, creating an extensive and remarkable recorded archive of her life. Lyden’s fascinating and intimate look at public and private photographs of the queen and her family provides surprises. One is that the young Queen was very conscious of how she looked to the public, and for instance, she scratched out an unflattering shot of herself with her family. Two days later, mindful of her duties, she poses again for the same composition. The private photos, which she never meant to be displayed, show her children in amateur theatrics as well as in groups, while others show a young queen with her hand familiarly on her husband’s shoulder. Victoria had pictures taken of her staff, going to the stables herself to see how the horses were posed.

Plate after gorgeous plate of lush photographs are provided, from Talbot and William Kilburn (who took the photograph that irked the queen), John Mayell, Roger Fenton, to Gustave Le Grey’s astounding open sea vistas and the dreamily posed compositions of Julia Margaret Cameron. The details of dress, which first drew the young queen’s eye, the soft lighting, and finely arranged portraits show the medium evolved to an art. Other plates demonstrate the Victorian enthusiasm for exhibitions and landscape; still others show the middle-class in photographs sometimes styled after the queen’s sittings. A lolling hippopotamus at Regent’s Park makes a surprising appearance.

This is a remarkable volume to spend many rainy afternoons with, as we see how the boundaries between the private and public fall away as modernism approaches. People love to see the faces of their friends, said Oliver Wendell Holmes, and photography answered that call in card-sized portraits to pass among social circles. The public also sees Victoria in all her life stages as queen, from young wife and mother, to her deathbed. Lewis notes, “Her funeral procession on February 2, 1901, was not just photographed but filmed; one can find it today on YouTube.” A glimpse of the photographs appear on the Getty Museum website and at the Royal Collection Online.

Novelist Indira Ganesan was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa at Vassar College in 1982. Her books include The Journey (Alfred A. Knopf, 1990), Inheritance (Alfred A. Knopf, 1998) and As Sweet As Honey (Alfred A. Knopf, 2013).