By Corey Wronski-Mayersak

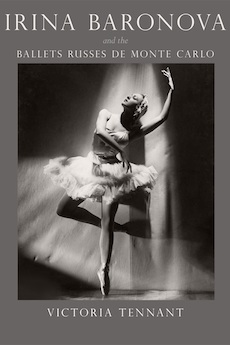

Just as beauty and elegance characterized prima ballerina Irina Baronova (1919-2008), those words also describe this emotional and visually stunning account of her life compiled by her daughter, actress Victoria Tennant. Far more than a biography, reading the book is like being invited for an intimate family chat. Tennant takes the reader through the boxes of historical photographs, family documents, and personal mementos that she poured over following her mother’s passing, and the reader shares in the immediacy of Tennant’s emotion as she reflects on what they reveal.

Baronova’s personal story – fascinating, glamorous, and inspiring in itself – is not the only story in view here. The book’s significance is far wider: it offers an account of the rise of ballet in the United States and the broader cultural history surrounding that development, told through the microcosm of Baronova’s life and relationship to the triumphs and struggles of the Ballets Russes. Thus Tennant’s book is not just for balletomanes, but valuable for all readers interested in the development of the arts in the twentieth century.

The Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo is credited with popularizing ballet outside of Europe and the British Isles, particularly for winning and then sustaining an audience for ballet in North America and Australia in the 1930s and 1940s. Tennant traces the development of the company from its formation in 1931 out of a partnership between Colonel Wassily de Basil and René Blum with George Balanchine serving as the company’s first ballet master and choreographer. Balanchine aimed to create fresh, new ballets (a shift from the lavish fairy tale and folk tale-inspired shows that were the standard set by Serge Diaghilev in the preceding decades), and he needed young new stars to do so. From a tour of Paris studios, he selected several young girls, among them the 12-year-old Baronova. Over the next few years, the company would develop the new form of abstract symbolist ballet, and would also expand ballet’s audience with tours through Europe, then the United States in 1933 and subsequent years, and then Australia and New Zealand in 1938. Tennant brings the reader on that journey, beginning with Baronova’s childhood as a Russian refugee, and extending through her career with the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo, her work in film, her role in the origins of American Ballet Theatre, and her retirement from the stage.

The Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo tours prompted a substantial cultural shift that is hard to overstate. As Tennant writes, “It seems extraordinary now, when every town has a ballet school and every little girl has a tutu in her dress-up drawer, that there was a time when ballet was largely unknown in America.” But that time was not long ago, when the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo undertook its first US tour. She recounts how one theatre manager the company met on the first US tour mentioned he had never seen a ballet before. Roughly ten years later, the production “Ballet Russe Highlights,” featuring stars of the early company, attracted tremendous audiences: one performance in Philadelphia had an audience of 15,000, and two New York performances attracted 25,000 people between them.

The story of the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo can be found elsewhere, including in Baronova’s own book, Irina: Ballet, Life, and Love (2006) and the documentary film Ballets Russes (2005). But Tennant’s account offers unique insight, bringing her perspective on the stories that her mother shared with her as a child and weaving together her own reflection and additional research with Baronova’s voice in several forms, for example in text taken from family correspondence and quotations from Baronova’s autobiography. The book’s narrative moves gracefully between these multiple voices, distinguishing Baronova’s words with gold font. The book beautifully demonstrates that we can never fully know the inner lives of those we love, and Tennant was on her own journey as she sorted through her mother’s papers, with numerous discoveries in the process – among the most poignant moments that Tennant recounts is her discovery that Baronova had lovingly preserved her toe shoes from her last performance.

Additionally, Baronova’s papers included over 2,000 photographs, a precious and engrossing visual testimony, and Tennant is able to enrich the story of Baronova and of twentieth-century ballet with this archive which, she writes, “told my mother’s story in pictures.” These include publicity photographs and images of Baronova dancing, of course, but also personal photographs of her extensive travels that document the times. Images of the company members traveling in the 1930s and 1940s offer a window into the cultural world of that era and its diversity. We see Baronova both at a 1930s Texas ranch and among the glamour of 1940s Hollywood; we see the Ballets Russes dancers on the beach at Monte Carlo, and also driving between American cities, with the images also showcasing the history of 1930s and 1940s fashion. The company members appear alongside key figures from the worlds of art (e.g., Joan Miró) and film (e.g., Clark Gable), with this visual record offering a sense of the reach of the company’s circle and its social and artistic impact on the twentieth-century.

Tennant says that she initially set out to provide “context” for her mother’s photographs; that is extremely modest compared to what she achieves in this interdisciplinary, cultural history. Irina Baronova and the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo is not only a story about a ballerina or ballet, but a valuable reminder of the immeasurable power of the arts to enrich public life.

Corey Wronski-Mayersak (ΦBK, Goucher College, 2002) is an Assistant Professor of English at McDaniel College and a resident member of the Delta of Maryland chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.