By Allen D. Boyer

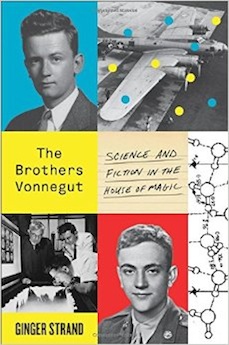

Ginger Strand (ΦBK, Kalamazoo College 1987) has written a winning book about a glistening American utopia and two gifted young men who began their careers there. They were brothers from Indianapolis who worked for General Electric after the Second World War: Kurt Vonnegut, who began writing fiction while working as a publicist for GE, and Bernard Vonnegut, a GE research scientist who essayed to control rain, snow, and fog by seeding clouds with silver iodide.

The setting was Schenectady, New York, world headquarters for General Electric, which claimed that “progress is our most important product” and called its fabled Research Laboratories “the House of Magic.” Outside the House of Magic lay the row houses of factory workers, the leafy avenues where GE executives lived, and the massive machinery of the Schenectady Works:

“A brick and steel compound ringed by a fence, the hulking, humming city within a city contained forty thousand employees . . . . The Works had a hospital, a fire station, a power plant, and a foundry. It had clubhouses, restaurants, employee stores, its own sound studios, and a radio station, WGY. Blinking down on all of it through the smokestack haze was the sign atop Building 37: yellow letters ten feet tall spelling out ‘General Electric,’ crowned by the giant red GE insignia.”

This book wears its learning lightly, but Strand has dug deep in the Vonnegut archives. She outlines where Kurt’s fiction echoes his work for General Electric. Kurt stole from GE research mandarin Irving Langmuir an idea that Langmuir had offered to H.G. Wells, the idea of a form of ice whose crystals would be stable at room temperature: the planet-killing Ice 9 of Cat’s Cradle. In Player Piano, Kurt’s parodies of corporate retreats are vicious satires on GE summer events – the pep-rally songs may even be lifted from a GE songbook. “The stories he wanted to write were GE stories,” Strand observes:

“He called it General Forge and Foundry, or General Household Appliance Company, or Federal Apparatus Company. But the company discernible behind all of them was the one he knew so well: the scientists, the PR hacks, the visitors on Works tours, the imperious managers, and the girl pool where typists Dictaphoned the days away, awaiting rescue by diamond ring. . . . Most of all he wrote about company attitudes: the worship of the company man; the mindless team spirit; the faith in progress, technology, and science; the enthusiasm for anything that reeked of the future – the machine-made, computer-coded, semi-conducted, radioactive future.”

As Kurt’s fiction invites, Strand’s insights are freighted with irony. Kurt wrote satire and whimsy with method and rigor. He typed in the evenings, meticulously noted rejections and editors’ comments, cultivated mercilessly a college friend who worked for Collier’s. He wanted to publish scathing social satire in The New Yorker, but he offered women’s magazines stories about war widows and turned to science fiction when pulp magazines embraced his work. He scheduled his time with Hoosier earnestness: “three days to revise a story, ten or so to write a new one. Ten days for the ‘Ice-9’ revision, and then there was his novel, Player Piano. He allotted three weeks for chapter 1.”

Bernard worked with GE’s Project Cirrus, which aimed to control weather masses. He flew cloud-seeding runs in war-weary B-17’s (bringing down floods and blizzards) and strung copper wire between mountaintops (reversing the polarity of thunderstorms). In family photos, he looks alert while Kurt looks dreamy. But if Kurt worked seriously at light literature, Bernard’s research could be playful. In the evenings, Bernard did backyard experiments: his family home would be wreathed in fog while the rest of the block enjoyed a clear evening.

For both brothers, in the end, utopia became dystopia. Kurt left in 1950, and wrote Player Piano, about a rebellion in a company town where machines had replaced human workers. It recalled Nineteen Eighty-Four and Brave New World and no bookstore in Schenectady would stock it. Project Cirrus closed, amid a tempest of lawsuits, and Bernard disliked being told to work on transistors. He left in 1952, eventually to teach at SUNY Albany.

Kurt Vonnegut said that he could not avoid writing science fiction, “since the General Electric Company was science fiction.” And although it is a biography, The Brothers Vonnegut reads like science fiction. It is set in an era when the military and heavy industry bestrode the nation, and a daring young scientist might bring down rain on dry country or carve swathes of blue sky in a grim, gray overcast. Its narrative unfolds in a lost world of typescript and bookshops and magazines, where an ambitious young writer might quit his day job once he had sold five short stories. Strand takes the measure of the milieu in which Kurt and Bernard worked, and suggestively measures the difference between that culture and our own.

Allen D. Boyer (ΦBK, Vanderbilt University, 1977) is a lawyer and writer in New York City. Vanderbilt University is home to the Alpha of Tennessee Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.