By David Madden

From 1935, midway into the Depression, to 1943, well into WWII, Roy Stryker, head of the Farm Security Administration sent a great number of photographers throughout the United States to document in images “the need for Federal assistance in mostly rural areas,” but also in cities.

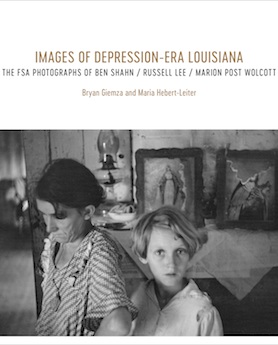

Stryker’s program was “a convergence of talent, leadership, and dedicated vision that resulted in one of the most impressive photo collections available to the general public.” Of the 170,000 negatives, the authors of Images of Depression Era Louisiana present 168, the work mostly of Ben Shahn, Russell Lee, and Mary Post Wolcott.

The text consists of only 29 double column pages, which includes 26 photographs to illustrate points about “the making of visual history” made by the Bryan Giemza and Maria Hebert-Leiter. In a prose one might wish were less pedestrian, they provide general factual background, interesting short biographies of the leader, Roy Stryer, and of the three quite famous featured photographers, Ben Shahn, also a major painter, Russell Lee, who took most of the photographs presented, using a special technique, and self-sufficient Mary Post Wolcott, former newspaper photographer in Philadelphia. The authors also briefly examine FSA photographs by Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Louisianan Clarence John Laughlin.

The text is more narrative than interpretive. The authors make a few rather perfunctory attempts to explain the importance, effect, and legacy for viewers of the photographs today, with a nod to ethnic and racial relevance; they make minimal use of current jargon, such as “enclosure,” some comparison of the photographers’ “vision,” and merely include the phrase “aesthetic content”:

“…Louisiana photographs… reward with new insights into the state’s history. Each image reveals something specific about the cultural and economic realities of a locale’s past…. [They] reveal the power of an image to speak across time…. We read the faces captured in these photographs for their personal histories and feel that they are among us still.”

The authors do not prove out, so to speak, the statements they make above. Further, they do not venture into the sometimes mysterious nature of photography, and how these photographs may suggest or reveal the sensibilities of the photographers in the choices they made.

Because beholders of the photographs in this collection have seen a good many of these photographs before, they will, I expect, crave analysis of greater depth, especially of individual photographs, such as Shahn’s woman and young girl, Lee’s “Negro musicians,” and Wolcott’s Spanish trapper.

My own many years of consciously responding to the whole range of photographs, including the great treasure of Civil War photographs, my published studies of photography, and my 41 years of living in Louisiana make me an ideal viewer of the photographs in this collection. None of these images of life in Louisiana seem unfamiliar to me. So I want this book to join a good number of other books of Louisiana photographs on my shelves.

But I am disappointed by the quality of the reproductions. They are uniformly somewhat grayish in tone, resulting in a disservice to the photographers whom the authors strive to celebrate. One hopes the authors complained. The responsibility lies with the printer and with the publisher. Even in many books lavishly illustrated with photographs, respect commensurate with that accorded other arts has yet to be fully enough conferred upon photographers.

Even so, this collection is somewhat uniquely inclusive and deserves qualified gratitude and praise.

David Madden (ΦBK, University of Tennessee, 1979) is the author of “The Cruel Radiance of What Is” in Southern Eye, Southern Mind, a Photographic Inquiry (Exhibition catalog) and “Photographs in the l929 Version of Sanctuary,” in Faulkner and Popular Culture, and of many books of fiction and nonfiction.