By Allen D. Boyer

In the summer of 1955, heart attacks staggered two of America’s most powerful politicians: Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson and President Dwight D. Eisenhower. This cataclysm in the political firmament, Thomas Oliphant and Curtis Wilkie write, suggested an opening for a new generation of politicians, and its reverberations were profound.

“It represented a spark, the first time national office was the subject of something other than formless ambition . . . and it ignited a five-year quest that culminated in Jack Kennedy’s transformative election as the country’s thirty-fifth president at the young age of forty-three.”

This year marks the centenary of John F. Kennedy, whose tragedy was never to grow old. In American memory, JFK remains forever boyish, forever stylish, and his forcefulness shapes this narrative: The Road to Camelot has the verve and energy of breaking news.

Oliphant and Wilkie track Kennedy’s drive to the White House, a campaign that was ambitious in every sense. In 1955, Kennedy was a minor figure in American politics, “considered more of a socialite and a war hero than a political leader.” In 1956 he made an upstart bid to gain the vice-presidential nomination, and failed. Thereafter, he worked less conspicuously and more earnestly. He made a quiet, sustained effort to lock up support from Democratic leaders across the country. In 1960, when traditional politicians focused on caucuses and state conventions, he focused on primary wins, and elbowed his way past a mass of presidential hopefuls: Adlai Stevenson, Stuart Symington, Wayne Morse, Hubert Humphrey, Lyndon Johnson.

Veteran journalists—Boston Globe reporters who worked together during eight presidential campaigns—Oliphant and Wilkie have built up this book from memoirs and interviews (some personally conducted, others from the oral history archives at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library). They skillfully pace the story, and handle succinctly the issues and engagements of the 1960 campaign: Protestant voters’ distrust of a Roman Catholic candidate; the surprising strength of Richard Nixon, who had cunning and guile and foreign policy expertise; and a late-in-the-day skirmish with white Southern politicians, which ended with Robert F. Kennedy making a phone call that freed Martin Luther King Jr. from a Georgia jail.

Particularly deft is the authors’ account of the Kennedy-Nixon debates. They dissect the lingering myth that radio listeners thought Richard Nixon won the debates, while those who watched TV broadcasts favored Kennedy. By 1960, they point out, voters who got their news from radio were “more likely rural—and thus more conservative, more likely Protestant, and therefore more likely to be Nixon-leaning.” If Kennedy won over the television audience, it was because he played to viewers. He had worked for three years with television experts.

“He had absorbed numerous pointers—that message and appearance are linked; that short, declarative sentences trump pseudo-erudite verbosity; that a dab of makeup improves appearance; and that under harsh stage lights blue shirts are better than white. He was still working on advice to slow his delivery and breathe with his diaphragm.”

JFK also pioneered the use of short TV ads. Previously, politicians had bought TV time to broadcast speeches, or used five-minute ads that cut off the ends of popular prime-time programs. JFK ran 30-second spots that brought his name to voters in key primary states: “It is likely that any West Virginian who watched television in the evening, and most probably did, saw at least one Kennedy commercial before turning in.”

Kennedy could not follow the contemporary strategy of energizing his base—playing only to groups he knew to share his values, while writing off (and denigrating) groups unlikely to vote for him. Kennedy had to win every vote he could—he had to appeal even to voters who looked unlikely to support him—and he did it, in every sense. He won voters’ attention with a wit and eloquence that reflected his keen, quick intelligence, and he made the most of his rare ability to appeal to voters’ highest instincts. Cutting through anti-Catholic prejudice (the most persistent roadblock) called forth some of Kennedy’s most memorable statements. At the Alamo, he told an audience of Baptist preachers in Texas, side by side with Bowie and Crockett had died men named Fuentes and McCafferty and Bailey and Badillo, “but no one knows whether they were Catholics or not. For there was no religious test there.”

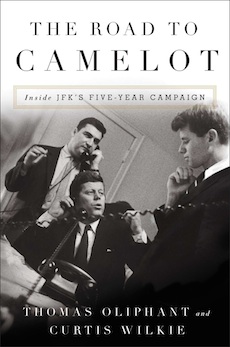

The Road to Camelot tells its story with little framing. There is no preface; there is no afterword; the book is an in-the-moment narrative, not a historical meditation. One well-chosen photo, however, suggests what Kennedy’s election meant. It was taken on the morning of January 20, 1961, and shows the outgoing president and the president-elect setting out together for Capitol Hill. Dwight Eisenhower and Jack Kennedy are dressed to the nines, complete with top hats. Their headgear is supremely elegant and ineffably stodgy. In half an hour, Kennedy would give his great Inaugural Address—warning of arms and burdens, talking of hope and light and freedom, challenging a new generation—and the day of top hats would be forever past.

Allen D. Boyer (ΦBK, Vanderbilt University, 1977) is a lawyer and writer in New York City. His fifth book, Rocky Boyer’s War, has recently been published by the Naval Institute Press. A previous version of this review was published by HottyToddy.com. Vanderbilt University is home to the Alpha of Tennessee Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.