By Svetlana Alpers

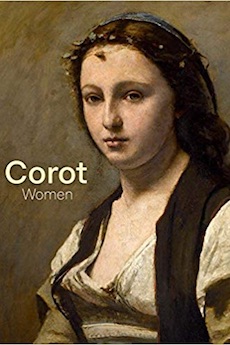

Returning to certain museums, one anticipates the joy of looking again at a marvelous painting of a woman by Camille Corot. The Met in New York has two: a modest woman seated in a landscape with her book, and the Sybille, as she is called—larger, grander, holding a pink flower (a Rembrandt woman with a pink is also at the Met) while gazing at us firmly, mysteriously, the paint looking still wet on her sleeve. In Chicago, another reader, this time lost in thought, is looking out, displaying beautiful arms. And perhaps best of all at the Louvre, a woman standing in the studio, not robed in an exotic costume like others, but in a contemporary blue evening gown, the coat removed to reveal the fleshy upper arm, which in our day, women sacrifice at the gym.

Though Corot made some repetitions, otherwise each woman is distinctive. All are painted in such a way as to hold the attention, though some strike me as distinctly better than others. They date from the 1850s and 50s, Corot’s last decades, and few were exhibited in his lifetime. He also painted female nudes, often situated in the disappointing landscapes of his later style. With the exception of one named by Corot as Marietta, they seem to me of less interest than the women who are clothed. The women were paid models whom Corot, so we are told, chose with care and treated with respect. The works are studio productions, though we otherwise remember Corot for the plein air landscapes of his early days in Italy. Working after life is the common thread.

This book was published to accompany an exhibition at the National Gallery in Washington, DC. It is a series of essays with illustrations rather than a proper catalogue. It is interesting that American collecters like the Havermeyers and Chester Dale had a taste for Corot’s women. And Alfred Barr of MoMA, always an intelligent eye, recommended a marvelous one for purchase by Smith College. Corot knew Italian art, but the women remind one of the Dutch, Vermeer in particular. Maybe that is why Americans who had a taste for the Dutch collected them.

I am not convinced by the attempt of the art historians writing here to place Corot and his women as anticipating the innovations of Cézanne rather than following Fragonard. He did neither one nor the other in my view. He was an independent, though dependent on a rich and complex tradition of European painting.

The task of looking at Corot’s women is to take them as they are. And the person who has done the best job of that so far is the poet James Merrill in his Notes on Corot. Here is a taste:

“One has the feeling of Venice and Delft being recreated at nightfall, on a rehearsal stage. The solitude of any Renaissance woman never bothered us; she sat at her ease on an invisible throne of philosophy and manners. In the Lowlands there was always the music lesson, or some household matter to be dealt with….The pomp and pride of one tradition, and the charming resourcefulness of the other are lacking in Corot’s women. The most they can do is look as if they were reading or able to pick out a tune; their minds are elsewhere, we feel anxious for them….These ladies could not say more than Corot what ails them….They are the last figures that a serious painter will ever render with that particular serious “studio” look….Their postures show what art has taught them to expect of life….Better to waste away, unloved, than to break faith with their creator. In the mercy of his brush salvation lies.”

Merrill’s essay is fine and true. It is to his credit that David Ogawa quotes from it here before starting his own essay.

Reviewer Svetlana Alpers, an artist, critic, and renowned art historian, is professor emerita of the history of art at the University of California, Berkeley and a visiting scholar in the Department of Fine Arts at New York University.