By Svetlana Alpers

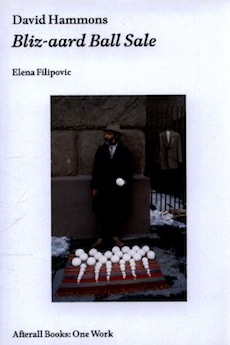

One wintry day in 1983 in New York, at Astor Place, a man laid a small blanket out on the pavement. On it he carefully set out about fifty perfect, round snow balls of several different sizes (they had been made in plastic molds) in a neat pattern. Standing behind the display to hawk his wares was David Hammons, the brilliant and secretive black artist who here, as always, was teasing, playing with, bucking the white art world, its makers, its market. People looked, were amused, were puzzled, some even bought. There is inevitably an aesthetic order and appeal to anything Hammons makes. A photographer friend was asked to photograph it all. The prints were made as a record of the sale, but the images were multiplied so they would have no value. “I sold ‘em’ cause I knew that people couldn’t hold’em’,” Hammons said of his snow-balls.

Filipovic, an art historian who is the director of Kunsthalle Basel, has written a smart book about the work of this great and evasive artist. The challenge for any art-writer is that Hammons refuses to be interviewed. He keeps his distance. Some years ago she was able to catch up with him for a short walk. At one point, placing Hammons’ behavior, she mentions Ralph Ellison and his famous novel Invisible Man. But while Ellison felt himself to be invisible to others, Hammons has made himself invisible as an act. It is the creative act that shapes his life and his work. Though he refuses almost all interviews, many comments and statements he has made are in circulation. Here is one: “I like being from nowhere: it’s a beautiful place. That means I can look at anyone who is from somewhere and see how really caught they are.”

Born in Springfield, Illinois, in 1943, Hammons worked in Los Angeles as a painter and printer off his own body in the early 70s, moving to New York city in 1974 where he has lived ever since. Though he has exhibited here and there, he has never accepted representation by a gallery, and when he does exhibit he often changes the things on view in the course of the exhibition. The art world system is there to be disrupted. In recent years, he has been shown by Robert Mnuchin in an elegant townhouse on 78th off Madison Ave in New York. (Though will he continue to do so now that Stephen Mnuchin, the owner’s son, is Treasury Secretary to Trump?) On one occasion, he draped dress-makers’ forms with splendid fur coats which had been moth-eaten, burned and torn—their great days past. On another occasion large abstract paintings were covered with bits of torn and bedraggled material. Seeing things of beauty and worth exhibited as detritus in the elegant Mnuchin spaces is dislocating: you are pulled up (the surroundings) and down (the art works) at the same time.

While keeping apart and staying invisible, Hammons has received many rewards. In the early 90s he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, a year at the American Academy in Rome, and finally, a MacArthur Fellowship. The first two require an application. Did he actually apply?

Hammons sympathy is with Marcel Duchamp, the French one-time painter who immigrated to New York and had a huge impact on the New York art scene: “I always admired the renegades. Duchamp and those cats. I’ve always thought the outside was the place to be.” Duchamp’s turn against paint and opticality was determining (unfortunately, I think) for American artists. What attracted Hammons was his outsider stance and his engagement with common objects in the world. But for Hammons beyond being an aesthetic matter, that was a political stance.

What Hammons makes comes out of the basic stuff of black life, often from the street: Phat Free is a stunning video of a black man (Hammons himself) kicking a can at night down a street in downtown New York; hair from a barbershop floor (a large sculpture made out of it at the Whitney); basketball hoops (Higher Goals were fancifully decorated poles set up on a vacant lot by Hammons and a bevy of friends dressed in tribal garb); High Falutin is a hoop, topped by a candelabra, in a museum; street dirt (outlining absent paintings on a wall with frame-shaped dirt); his urine sprayed on Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc, naming the gesture Pissed Off. He is as much a wizard with words as with materials. The words are targeted at the white world he finds himself in.

Reading this book I was surprised not only by Hammons’ extraordinary energy but also by what I sensed to be his anger—anger towards the American world in which he and other black people live. When I remarked on that to an African-American curator who sat next to me at a dinner, he exploded—Had I ever met Hammons? How, he asked, did I know that about him? I was firmly put in my place. Perhaps I don’t know.

We are living at a moment when many makers, groups of makers, of over-looked art are being brought out and exhibited. Women and African-Americans are among the newly discovered once-ignored groups. The market wants them to sell. One wonders what Hammons thinks about it. His sense of himself, his tactic, is to censure and avoid the very market that the overlooked artists are being brought into.

Reading this book will help you get to know a hugely impressive artist among, or it is rather apart from, us.

Svetlana Alpers, an artist, critic, and renowned art historian, is professor emerita of the history of art at the University of California, Berkeley and a visiting scholar in the Department of Fine Arts at New York University.