By Louis J. Kern

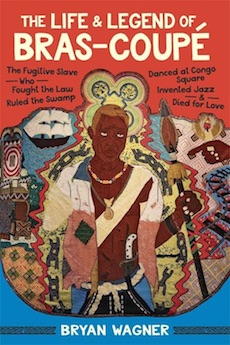

Wagner’s comprehensive introduction provides a context for the documentary evidence—newspaper accounts, police records, and oral tradition—and a critical assessment of a wide range of literary re-imaginings (1830s to 1960) of the story of the runaway slave Squire, known as Bras-Coupé. Facts are sketchy: Squire fled the DeBuys’ plantation in 1835 and joined a maroon community in Bayou St. John. Assembling a gang, he became a notorious brigand. In 1836, pursued by police, he was wounded in the left arm; infection necessitated amputation. He escaped, fled to Bayou Metairie, and was cowardly murdered there by an accomplice in July 1837.

A shaky foundation for the construction of a prominent figure in New Orleans oral tradition. But as Richard Dawson noted (American Legend, 1971), from a confluence of historical and imaginary roots, “legends alter and reshape the personage from history to suit the folk imagination, while historical setting forms around the created figure who will be regarded by the folk as a real-life superman.” In African-American folklore Bras-Coupé became a heroic rebel slave, a leader of the borderlands maroons, an isolate misanthrope and heroic avenger, a superhero of gigantic proportions, a trickster, a cannibalistic bogeyman, and a channel for zombie and voodoo infiltration. He joined the folkloric ranks of Annie Christmas, the supernaturally strong keelboat captain, the Kaintock, a half-animal hobgoblin, and Compé Lapin, the Haitian trickster. Abolitionists envisioned him as an exemplar of liberation from oppression.

For whites, in the years following Nat Turner’s rebellion (1831), the threat of servile insurrection loomed large. Consequently, ignoring the harsh brutality of slavery, they saw Bras-Coupé as a dangerous robber, murderer, and rapist, a dire threat to civilization itself. After Reconstruction, white authors romanticized his life; the earliest was George Washington Cable’s historical novel The Grandissimes (1880). The sentimental tale is set in the 1790s. “Jim” (Bras-Coupé), depicted as an African prince, has a tragic love affair with “Palmyra.” He is captured by the police while dancing in Congo Square and as a runaway his ears are cropped, he is hamstrung, and is severely beaten. He dies on his old plantation believing he would return to Africa. Here Cable is sympathetic to slaves’ quest for freedom, but elsewhere he depicts Black music as savage and dancers like monkeys (“The Dance in Place Congo,” 1886). Local historian Henry C. Castellanos’ version (1895) is essentially an apologia for slavery, extolling the benevolence of masters, the improvement of slaves’ condition under plantation management, and the crueler circumstances for slaves under African masters.

Subsequent accounts follow the heroic and romantic lead of Cable. Frederick Delius’s opera Koanga (1899), libretto by C.F. Keary, is hyper romantic, ending with Palmyra’s suicide, while Robert Penn Warren’s Band of Angels (1955) presents a super heroic “Rau-Ru” who survives the 1830s, fights for the Union during the Civil War, and becomes a Reconstruction official. It was cinematically recreated in Raoul Walsh’s Band of Angels (1957).

Sidney Bechet, jazz virtuoso, claimed Bras-Coupé (“Omar”) was his grandfather and retailed the romantic story of his legendary life. He argues that Bras Coupé’s dancing and singing in Congo Square, sparked by the cry of “Dansez bamboula! Badoun, badoun!” initiated the rhythmic, syncopative, and spontaneously innovative elements that comprised the basis of ragtime and jazz.

This volume reclaims a little-known legendary African American figure whose relevance may be seen in contemporary poetry and fiction as well as the iconography of the Mardi Gras Indians. Wagner’s essential critical collection of texts gives us a slave-era folk hero to join the free-black, working class John Henry and the underworld Stag Lee in the pantheon of African American folklore.

Louis J. Kern (ΦBK, Clark University) is professor emeritus of history at Hofstra University. Hofstra University is home to the Omega of New York chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.