By Indira Ganesan

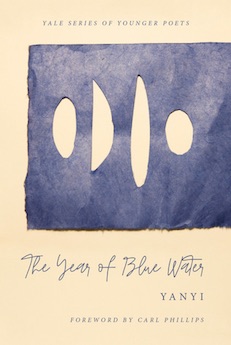

The foreword to The Year of Blue Water by Yanyi is written by Carl Phillips, the poet and judge of this year’s Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize. It is a celebratory and sensitive assessment of this quietly assertive, nuanced book. I suggest you skip it to savor after reading Yanyi’s book. What I suggest is that you read the poems without knowing the plot, letting the poems build and fall in their natural rhythms. We begin with a dream:

“You’re awake, then you are standing.

Then the last thing that you dreamed will unfold

its field of memory. What you touch will come

to life: a whole room sprung in the backwards words

of people untalking to you….”

This is language catching deliberately the way it feels to move through a dream, and how the dream reveals and unravels what is true in life. A poet wakes and writes it down, rearranging the words to reflect what has occurred, and initiates the reader into what will occur in the following pages as well. Life is ephemeral, filled with ghosts, and as Yanyi reminds us, and himself, “you are language, too.” And language is changeable, in the way bodies and thoughts are changeable, mutable, and capable of stretch, accommodation, and resistance.

Yanyi has composed a book that alternates prose poems of memory, of reality, with small abstractions, as the poet ponders words other artists have said. A mediation that begins:

“at lunch my body didn’t want food. It wanted

fries or peanut M & Ms; they were a dollar instead of two, the

price of a high school lunch. I saved money this way. I wasn’t

sure what I was saving my body for….”

It is followed as if in academic translation on the next page by:

“Robin Coste Lewis describes beauty as a field of power. The

search for land, for possession, for domination, is all in service

of a search for pleasure.”

The poems, like the body, are political, ripe for possession, abandonment, transformation. The transgender is addressed in parentheses, not as afterthought, necessarily, but as some alongside the heady quest for meaning. Community is key here, for Yanyi as any artist is aware that nothing is possible without the ideas, ballast, provided by friends, just as other voices, like that of dancer Agnes Martin, and poet Robert Hass, are read for meaning, as springboards.

“My research is a combination of advice column, comprehensive

Sex-ed websites for teens, and horoscopes. There is an entire

Stream of emotional knowledge regulated to the darker depths of

The Internet…I reread the definition of love: compassion, respect, accountability.

Strategies for your sexual self. What to know about an Aries…

Taking quiz after quiz, personality test after personality test,

trying to reach the person I wanted to be.”

If this is not genius, of clarifying what it means to be immigrant, different, of wanting to belong, yet recognizing the ludicrous nature of such a quest, yet plunging ahead anyway, then I don’t know what is. Read The Year of Blue Water. It is a slender wonder. It is a book that, as Carl Philips notes, acknowledges “a hope born of courage and generosity, out of which Yanyi has made a book of wondrous changes, art, a life.”

Novelist Indira Ganesan was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa at Vassar College in 1982. Her books include The Journey (Alfred A. Knopf, 1990), Inheritance (Alfred A. Knopf, 1998) and As Sweet As Honey (Alfred A. Knopf, 2013).