Winner of the 2019 Christian Gauss Award

By Indira Ganesan

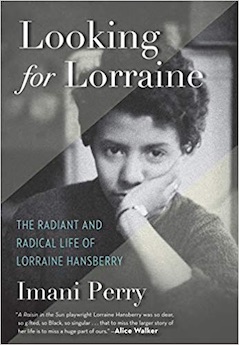

Imani Perry has written a remarkable book in Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry. Like Alice Walker did in search of Zora Neale Hurston, and as Isaac Julien did in search of Langston Hughes, Imani Perry goes in quest of a life lived and sustained by a writer who had a profound influence on American literary arts, and about whom so little is known. Lorraine Hansberry is the author of A Raisin in the Sun, the most widely produced and read play written by a Black American woman. Heartbreakingly, she died of cancer in 1965, six years after the show premiered on Broadway, after successful runs in Chicago and Philadelphia. She was 34 years old. Perry writes that this book is “less a biography than a genre yet to be named—maybe third-person memoir.” In many ways, it is a contemporary approach to a person gone missing from our lives, a link in a history of not only American theater but social protest theater. It is about a young writer, Imani Perry, searching for herself among her writing predecessors.

Similarly, Hansberry found herself talking at length with French feminist Simone de Beauvoir in her mind, trying to find her way and place in a deeply male world of letters. Who were the great American writers of the time but Hemingway and Fitzgerald, Kerouac and Mailer and Roth? Mary McCarthy and Lilian Hellman were tolerated, and Eudora Welty and Flannery O’Connor wrote short stories. So here is Hansberry, about whom Nina Simone sang “Young, Gifted, and Black,” a fierce warrior and defender of freedom, who suffered from debilitating depression, who married a Jewish white Communist songwriter, who was lesbian and radical, and would be celebrated by Vogue and called upon Bobby Kennedy for advice.

She wrote two more plays in addition to Raisin, a screenplay for a television mini-series that never aired, numerous short stories including a few under a pseudonym for chiefly gay journals. She wrote in response to what James Baldwin wrote, and he wrote in response to her. She was a relentless political organizer, and only illness prevented her from attending the March on Washington in 1963. As Perry tells us, she protested “the present and insufferable idea of the ‘exceptional Negro.’ Fair and equal treatment for Ralph Bunche, Jackie Robinson, and Harry Belafonte is not nearly enough. Tea parties at the White House will not make up for 300 years of wrong to the many. The boat must be rocked for the good of all.” How Hansberry told Bobby Kennedy off in the White House makes for fascinating and inspiring reading but is only one chapter in the life Perry uncovers through painstaking research over seven years.

She was many people, and encompassed many pieces, including being raised middle class and stepping out of cultural expectations. As a Provincetown year-rounder, I was excited to learn that Hansberry had visited and connected with the landscape and creative nourishment of my town. In Greenwich Village, she had met Molly Malone Cook, who would later become Mary Oliver’s long-time partner. Perry describes the photographs that Cook took of Lorraine conveying both an intimate and painterly knowledge. Somehow, Lorraine was able to extend herself easily both to her husband and her lover, as she could write for Broadway and for radical protest. A pervading sense of generosity existed in these lives that could accommodate difference and art.

Dying of cancer, a disease whose name was kept from her and her friends, as the custom of the times which tried to protect the one suffering from the its terminal nature, she was kept company in the hospital by her ex-husband, whom she had amicably divorced, together with her once long-time partner, Dorothy Secules. Hansberry’s funeral was attended by more than 700 people, with writers and artists whose names we recognize because we know so much about them. James Baldwin (who was one of her best friends), Paul Robeson, Ruby Dee, Dick Gregory, Shelley Winters, John Oliver Killens, Rita Moreno, and risking his life by coming out of hiding, Malcolm X. They knew what Imani Perry lets us know, which is the breadth of Lorraine Hansberry’s talent and humanity.

American theater, as any theater, really, has roots in radicalism, more so than literature. Performance is activism, after all. And researching and publishing the life of a luminary of American arts is activism, too, and I am grateful we have writers like Perry who has the foresight and sense to bring Hansberry into our line of sight again.

Novelist Indira Ganesan was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa at Vassar College in 1982. Her books include The Journey (Alfred A. Knopf, 1990), Inheritance (Alfred A. Knopf, 1998) and As Sweet As Honey (Alfred A. Knopf, 2013).