By Svetlana Alpers

The purpose of this magisterial book is to introduce us to Roger Fry’s writings on Italian art. Fry (1866-1934), a painter, sometime museum curator, founder in 1909 of The Burlington Magazine (a publisher of the present book), critic and famed lecturer, is best known for his pioneering 1910 and 1912 London exhibitions of Cézanne and the new French post- impressionist painters and his critical writing with its emphasis put on form versus content. This book focusses instead on Fry’s hugely articulate writing on (mostly early Renaissance) Italian painting. A major point of the book is that contrary to what has been thought, it was not that the new informed his view of the old, but that the aesthetic taste Fry had for contemporary painting had been developed earlier in looking and writing about the Italians.

But Caroline Elam has fashioned a book that turns out to be more than a collection of Fry’s hard to find critical writings on Italian art. Part II of the book is that, and it makes for invigorating reading from Giotto di Bondone all the way, surprisingly, to Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. As a whole the book offers an education in and an experience of the temper and tone of the professional world of people in England, the continent, and in America (where Fry, unhappily, worked at the Metropolitan Museum 1905-10) who were concerned with Italian art. It looks back to his predecessors Giovanni Morelli (1815-1891) a connoisseur with a system, and to the critic/advisor to dealers Bernard Berenson (1865-1959) even as it focusses on Fry, a member of that special English breed of critic/ painter that later came to include Lawrence Gowing and Adrian Stokes (might one add John Berger?) and looks back (in Fry’s case uneasily) to John Ruskin who wrote but also drew and painted. Chapters dealing with this rich, lived world lead up to the texts printed with the ample introductions and scrupulous annotations with which Elam fills us in on looking and thinking about Italian art in the years from Fry until her time.

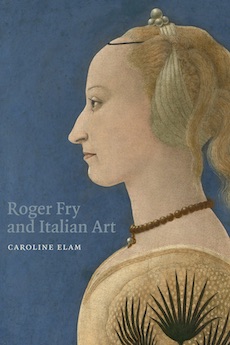

As you enjoy marvelous color plates which make even the smallest image in this book fully legible, it is salutary to remember that though the painter Roger Fry was acutely attentive to painters’ mediums and to color, every image that he showed in lectures or printed in publications appeared only in black and white.

At certain moments I, myself an art historian and critic, felt overwhelmed by the immersion this book offers into the small, dense, informed world of people interacting one with the other over and over again about Italian painting. This is what finding, identifying, and attending to these pictures was like. But then one reads Fry’s words.

Here he is (1924) describing Ludwig Mond, a private collector of distinction who gave pictures to the National Gallery in London:

They did not reveal their beauties easily or at first glance to the casual visitor . . . they are not of the kind that would ever be easy for a committee to buy.

Or, of two late Sandro Botticelli predella panels (an artist Fry otherwise did not have a taste for) these marvelous observations:

Nowhere do his figures press the ground with their full weight, and under the stress of passion they are swept forward by an inner impulse as we are in dreams, and float rather than walk, trailing their feet after them along the ground rather than using them as instruments of progression. –and there is more.

Or facing up to Andrea Mantegna in 1902:

The fact remains that those artists whose appeal to the imagination acts by arousing associated states ideas of terror and awe, do exert upon us a stronger and more ineffaceable impression than those whose approach is by seduction and charm.

Or, surprisingly arguing (1908) against Bernard Berenson, for a possible alternative tradition:

That Pisanello gave up altogether perspective, so nearly established by his trecento predecessors, would alone suggest that he had in view an altogether alternative mode of expression, one from which European art has studiously turned aside, but not, therefore, a negligible one.

Or, alternatively, arguing for perspective in Paolo Uccello’s Hunt in the Forest that glows and amazes in the Ashmolean and appears here as the endpapers of the book:

It is a most fascinating picture: the infinite recesses of the night woods, the stream gleaming thru the trunks of the trees, the canopy of leaves and night sky, and then the richness and intensity of life which suddenly invades the stillness, the shouting huntsmen in blazing scarlet and purple coats, the bewildering dance of hound and deer, show that even perspective had not dulled Uccello’s appetite for life in is most clamorous moments.

And ever attentive to the working of paint, Fry noted (as I a longtime lover of this painting had never noticed):

. . . the fingers that are everywhere marked by separate single strokes of liquid brush.

One wants to own this book for the possibility it offers to read such writing, and also for the story of how it was that such writing came to be written in the England of one hundred years ago.

Reviewer Svetlana Alpers, an artist, critic, and renowned art historian, is professor emerita of the history of art at the University of California, Berkeley and a visiting scholar in the Department of Art History at New York University.