By Indira Ganesan

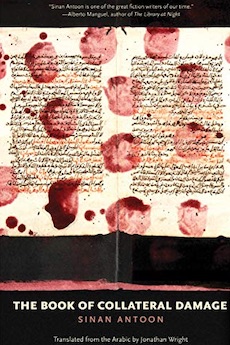

The Book of Collateral Damage is a searing book of indictment against war which will leave you thinking about it long after you finish. Sinan Antoon, a poet and novelist, is regarded as one of the most acclaimed writers in the Arabic world. Born in Iraq, which he left after the Gulf War, he has written three novels before this one, as well as several volumes of poetry. Growing up in a country where “poetry was as common as bread,” he was witness to the ravages of war first-hand. In this, his fourth novel, he gives us a timely account of life in wartime.

His protagonist, Nameer, is a student and teacher working in the U.S. who returns to Baghdad as translator to a pair of filmmakers shooting a documentary. While there, he encounters a bookseller named Wadood, who he learns is compiling an enormous book listing the effects of war as witnessed not only by people but buildings and animals. We open with a little bird learning to fly and follow the charming narrative of an innocent who will all too likely become a by-stander victim of man’s violence.

Lately, our screens have been full of the fleeing wildlife of Australia trying to escape the fires unequivocally caused by man’s effect on the climate.

A billion (think about that number for a minute) animals have already died. Now imagine the war in Baghdad where not only people are collateral damage, but structures and homes. Remember Snug, one of Bottom’s players in A Midsummer Night’s Dream imitating a wall, providing a chink for the lovers to spy each other? After acting its part, the wall solemnly bids adieu to the audience, as its part is over. I think of the whimsy of Shakespeare’s play in contrast to the wall Wadood depicts in one of his chapters, which watches as a child grows in a house. Once we connect to this most inanimate construction, we can feel the pain of the wall watching powerless as the child is shot along with his family. Soon, we know, the wall itself will crumble. This is the collateral damage of war, touching everything in its path.

In addition to the painstaking accounts Wadood records, we also follow Nameer. In Baghdad he is viewed with suspicion and scorn by fellow Iraqis for leaving, with hasty appreciation from a family that misses him, and with concern by his new girlfriend. We watch the subtle politics of being Iraqi in American academia, of the damage that reading Wadood’s accounts have on him, resulting in insomnia and reluctant trips to a therapist. Wadood writes that “sadness is a natural compound found in our bodies and in the air that we breathe,” rendering us all culpable. Depression too is collateral damage, for how could it not be? Who knows what effect not only the expectation and actuality of missiles in the sky have on the surviving, but the poisonous atmosphere in which news media are denounced and lied to? In other words, I wonder what the post-traumatic effects of living in the U.S. post-2016 will be for the ordinary citizen, because war is invisible and pervasive. But this book is about Iraq under Saddam Hussain, about the Gulf War, and about how very ordinary people watch their lives being blown away.

Sinan Antoon has asked us to consider the space that exists after death. He does this by building a collage of images and insights that break your heart again and again. He does this quietly, without theatrics. No one wants to confront war or malaise. People either run away from the past, or run to it, he observes. But our present lives, as a result, are experienced sleep-walking, moving from one place to another. Wadood stops time. He keeps account, creates stories as they are lived, and places our lives under attention. It is a powerful means of examining what we are made of, and how much will be taken away. The Book of Collateral Damage is a profound meditation on war, and I urge you to read it.

Novelist Indira Ganesan was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa at Vassar College in 1982. Her books include The Journey (Alfred A. Knopf, 1990), Inheritance (Alfred A. Knopf, 1998) and As Sweet As Honey (Alfred A. Knopf, 2013).