By John McWilliams

Reviewers strive to appear impartial and objective; they prefer that readers ignore Henry David Thoreau’s dictum that, in writing, it is always the first person who speaks to us. My motives here are partial and subjective. The 1965 NET Cambridge Union debate between Baldwin and William F. Buckley remains the most riveting television experience I have ever had. It made me an avid reader and admiring teacher of Baldwin’s writings for the next fifteen years, though I would never write about him. At age 81, I now need to confront Baldwin whole and in retrospect. Eddie Glaude’s direct, compelling book provides the perfect opportunity.

Another daunting provocation is that Baldwin increasingly felt a scornful pity for armchair white liberals like me. His Harper’s essay on Martin Luther King (1961) observes that “much of the liberal cant about progress is but a sentimental reflection of this implacable fact” (that the Negro vote still has no power because whites will never give their power away). The Fire Next Time (1963) refers to “the incredible, abysmal and really cowardly obtuseness of white liberals.” No Name in the Street (1972) recalls the McCarthy era as a “foul, ignoble time,” remarking that “my contempt for most American intellectuals and/or liberals dates from what I observed of their manhood then.” Liberals like to feel good but they do not act. After 1970 Baldwin became increasingly shrill about the need for everyone, but especially white liberals, to confront their origins, to bear witness, to reexamine their lives and racial history and, in short, to “do your first works over.” I have not done so nor have I acted.

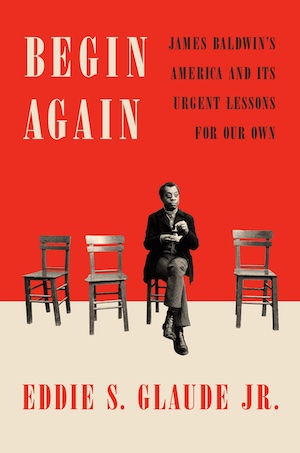

Enough confessional. Glaude’s introduction “admits” (not at all defensively) that he has written a “strange book”—not biography, not literary criticism, not history, but a deliberate interweaving of the three pointed at the present. By alternating Baldwin’s moral message with the discouraging failures and enraging atrocities of American culture since Baldwin’s death, Glaude urges Baldwin’s perspective and insights upon his reader. In this regard, Glaude’s book best fits into the national subgenre that Sacvan Bercovitch titled The American Jeremiad. Unlike Bercovitch’s Puritans and his early republicans, however, both Baldwin and Glaude write with subtle irony and a biting sense of humor that palliate dismissive condemnation. Because their readers must themselves choose to act, readers are to be persuaded first and then directed, but not commanded.

Glaude does not consider Baldwin’s fictions, effectively substituting for them passages from Baldwin’s speeches, reviews, and films, many of them little known. The celebrated early Baldwin of Notes of a Native Son, Nobody Knows My Name and The Fire Next Time is assumed to have been read. Glaude concentrates instead on the lesser known writings of what he calls the “after times,” after the Civil Rights Movement and desegregation had stalled, giving rise in the 1960s to assassinations, Black Power movements, inner city burnings, Reaganism, and continuing white intransigence. These were, for Baldwin himself, years of remaining what he called a “transatlantic commuter,” when his increasing bitterness could be met only by insistence upon a love extended beyond black and white, beyond all creeds and altars. His troubled hope was for a future interracial democracy of which he never quite despaired. Baldwin’s late life perspective, Glaude argues, must become both our heritage and our hope, our way to begin again.

The heart of Glaude’s book is a cumulative account of division and decline toward Trumpism, together with his own telling perceptions of it. Here are just a few of the markers: within the culture, the failure of the Poor People’s Campaign, “Medgar, Malcolm, Martin dead,” white flight, Watts, the inevitable suppression of Black Power, the rise of the Republican South, violent protests with little change, and continuing inequality of income, housing and schooling. From Baldwin’s writings, the following passages ordered sequentially: 1956-1961 seem “sad and aimless” years; “The vote is not the answer;” “The country does not know what to do with its black population;” “Morally, there has been no change at all;” Color is “a most disagreeable mirror,” also a “curtain of guilt;” “I’m black only as long as you think you’re white;” “There is not a single institution in his country that is not a racist institution” (today’s “systemic racism”); “The price the white American paid for his ticket was to become white—and, in the main, nothing more than that or, as he was to insist, nothing less.” Underneath them all is the “lie” of “white racism” based upon the self-destructive innocence of its true believers.

It is a commonplace to say that the “we” of Baldwin’s early writings dropped away, to be replaced by an open acknowledgment of a racially split population and readership. Less recognized is the fact that Baldwin was never to abandon the root conviction of the first sentence of his first review in 1947: “Relations between Negroes and whites, like any other province of human experience, demand honesty and insight; they must be based on the assumption that there is one race, and that we are all part of it.” Here is the earliest instance of Baldwin’s gradually abandoned “we.” Must it now be entirely abandoned from our usage?

Glaude’s cross-genre prose style creates a problem of narrative voice. Consider this passage: “As he [Baldwin] wrote in The Fire Next Time, ‘as long as we in the West place on color the value that we do, we make it impossible for the great unwashed to consolidate themselves according to any other principle.’ It makes all the sense in the world, then, that black people would look to the fact of their blackness as a key source of solidarity and liberation. White people make black identity politics necessary. But if we are to survive, we cannot get trapped there.”

Who is speaking the three sentences after the quotation? Is it James Baldwin, Eddie Glaude speaking for James Baldwin, or a fusion of the two voices? Glaude repeatedly writes as if he and Baldwin’s voice were and are clearly one; there are at least ten passages in which the two meld in this manner. The same practice can be found in exhortative protestant preaching and in quotation of passages in Jeremiads. But what of its use here? Baldwin repeatedly wrote about “individuality” in a sense very like Erik Erikson, who probably influenced him. Baldwin identified himself repeatedly as a “poet” or a “poet in prose.” Glaude, by contrast, is an eminent scholar and an influential academic. Begin Again has no footnotes. So, is it merely pedantic to say that Glaude’s reader should be given ways of knowing where Baldwin’s voice ends and Glaude’s begins? In fact, their two voices are not one; they need each other, but remain separate.

Although there seems to have been a recent Baldwin revival of sorts, Baldwin’s perspective and his formidable presence deserve still more consideration, still higher stature. Glaude’s book goes a very long way to restoring to Baldwin the continuing significance he deserves. How great the loss, then, that Glaude’s reader may close his book wishing that the author had offered specific solutions to America’s failure to solve what was once called “the Negro problem.”Reexamining the roots of our systemic racism, white and back, individual and collective, is necessary and good, but it must lead to widespread societal, political, and legal change. In his last chapter, Glaude calls for “a new American story, different symbols, and robust policies to repair what we have done,” then immediately adds, “I don’t yet know what this will look like in its details—and my understanding of our history suggests that we will probably fail trying—but I do know that each element is important to any effort toward beginning again.” Who better than Baldwin and Glaude to propose those “details,” but detailed proposals are not there in the texts of either author. Certainly, the writer of this review will not live to see them in practice. Let us hope Glaude is wrong to predict that “we will probably fail trying.” If we fail trying, there may be an even bigger fire next time.

John McWilliams (ΦBK, Princeton University) is emeritus professor of humanities at Middlebury College and a resident member of the Beta of Vermont chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.