Robert E. Lee and Me is history and confession wherein a credulous son of the South slowly comes to understand that Lee was not the Perfect Christian Gentleman of Lost Cause myth but instead a defender of slavery, a believer in white supremacy, and a traitor to the United States of America.

Ty Seidule, for two decades a member of the history department at West Point and now retired from the U.S. Army at the rank of brigadier general, was born in Alexandria, Virginia, where he grew up reading and rereading the Random House Step-Up Book Meet Robert E. Lee, Walt Disney’s Uncle Remus Stories, and Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind. In school, he studied textbooks that glorified the Confederacy and its Lost Cause defending states’ rights and the “southern way of life.” When his family moved to Monroe, Georgia, in his mid-teens, he attended George Walton Academy, one of the approximately eighty “segregation academies” founded in Georgia to frustrate the goal of integration. He writes of “growing up believing a series of lies about the Civil War and its legacy.”

Only much later did Seidule realize that the “southern way of life” was “white ladies and gentlemen sipping iced tea on the veranda under the shade of magnolia trees supported by enslaved workers” and that the Lost Cause myths were its justification. The Alexandria city council enacted a law in 1953 requiring that all new streets running north and south be named to honor Confederates and repealed it only in 2014, after 66 streets had that honor. In Monroe, one of the main streets bore the name of the county’s notorious Ku Klux Klan leader, William Felker. Seidule now calls southern plantations “forced labor farms” and the KKK “violent terror to enforce racial domination.”

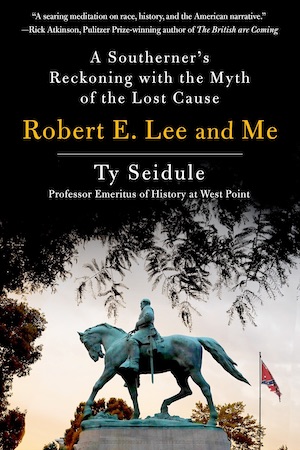

But before experiencing this epiphany, Seidule attended Washington and Lee University, the “shrine of the Lost Cause.” There in Lee Chapel, the “Westminster Abbey of the South,” a recumbent statue of Lee takes the place of an altar. And there, Seidule, as an ROTC cadet, took the commissioning oath as he became a second lieutenant and began what became a 36-year career in the army. By virtue of his four years at Washington and Lee, he was an officer and a gentleman and a legacy of the Old South. His first two postings were Fort Bragg, named for a slave-owning Confederate general from Louisiana, and Fort Benning, named for a slave-owning Confederate general and rabid secessionist from Georgia.

The epiphany about the Lost Cause and Lee did not come until Seidule, with the army’s blessing and support, earned a doctorate in military history at Ohio State University and joined the history faculty at West Point. He discovered that the nation’s military academy had a Lee Barracks, a Lee Road, a Lee Housing Area and a Lee Gate. Yet for the first half century after the Civil War, West Point called the fighting the “War of Rebellion” and denied the Confederate dead any memorialization. The increasing power of southern politicians, who could hold the academy hostage over its budget, influenced the change. Reaction against integrating West Point was a second factor: as African-American cadets increased, so did the naming of anything and everything after Lee.

Seidule finally applied his historian’s training to Lee’s reputation. His conclusion is as blunt as it is inescapable: Robert E. Lee violated Article III, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution and thereby committed treason. Lee resigned his commission, fought against the nation whose constitution he had sworn to support and defend, and was responsible for the deaths of more U.S. Army soldiers than any other enemy officer in any other war. The West Point motto, “Duty, Honor, Country,” adopted in 1898, was an affirmation of the oath that Lee violated. Of the living graduates in 1861, four-fifths remained faithful to that oath. Of the living graduates from the southern states in 1861, half remained faithful to that oath. Of the eight officers in the state of Virginia holding the rank of colonel in 1861, seven remained faithful to that oath; Lee, the eighth, alone violated his.

Most of Lee’s extended family rejected the Confederacy, as did many of his closest friends. What was his motivation? For Seidule, the answer is that Lee “committed treason to perpetuate slavery.” He was a wealthy slave owner known as “a hard taskmaster.” He loathed abolitionists for threatening his prosperity. When he learned of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, he wrote to the Confederate secretary of war that they were left with “no alternative but success or degradation worse than death, if we would save the honor of our families from pollution, our social system from destruction.” In 1868, three years after surrendering at Appomattox and then president of Washington College, he declared that the freed slaves had “neither the intelligence nor the qualifications. . . for political power.”

Seidule writes in his introduction: “I must do my best to tell the truth about the Civil War, and the best way to do that is to show my own dangerous history.” He has succeeded brilliantly.

Benjamin Franklin Martin (ΦΒΚ, Davidson College, 1969) is Price Professor of History Emeritus at Louisiana State University; his most recent book is Roger Martin du Gard and Maumort: The Nobel Laureate and His Unfinished Creation (2017).