By Svetlana Alpers

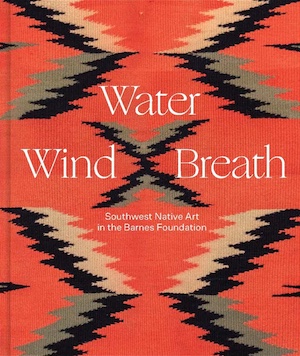

Every visitor to the Barnes Foundation is struck by the unusual mix of objects on display—yes, we expect multiple Cézannes, Matisses, and Renoirs, but there are also Shaker metal hinges attached to the walls between the paintings and Native American weavings on walls and shaped and painted pots and silver jewelry set forth in cases. Albert C. Barnes’s will and taste brought it all together, but it is the magic of a museum, in this case his museum, that offers us the space and time to look.

This book comments on and catalogs the 239 Native American objects that Barnes discovered and brought back to Merion from three trips he made to the Southwest in 1929, 1930, and 1931. He went there first, as many who could afford it did in those years, for what sun and dry heat would do for the health of his wife. But then he returned for the art and finally for a unique annual dance. He was surprised by it all, drawn to it, and bought with love, care and, most important, with careful documentation of what he spoke of as art-life—a Dewey-like notion of art as something richly-lived.

The Barnes has an impressive record of publishing its collection. This is another such—with stunning photographs and detailed catalogue descriptions which make the reader/viewer aware of materials. We attend to the way threads, clay, metal was worked by its makers. At a time when some contemporary artist have made a virtue of de-skilling, it is compelling to observe, by contrast, an artistic culture in which skill was essential.

But there is an unease here that is worth considering. The text also has the aim of telling us what Barnes did not see. That, one gathers, is the essence of life for the makers of the art expressed in the three words of the title—water, wind, breath.

In the book, you will find a juxtaposition of descriptions of ongoing Native American art and art-making by practitioners alive and working today, with the objects, and catalog of the objects, that Barnes collected. So, two different ways to make an approach.

It brings up an important question—do we often attend to the essence of the life of makers of the objects we see in a museum?

Barnes is described early in the book as a white male with money who (therefore?) necessarily saw the Native American objects from a distance. But isn’t distance part of the way we view any, indeed all art? Art indeed shows us that other people are different, and it encourages us to come to terms with and accept things that are strange. The strangeness is part of the experience of a marvelous Native American woven pattern, the signs, as they seem to us, painted on a pot, the squash blossoms extending out from a necklace of silver, or (to jump back in time) the bodies and landscape in a panting by Bellini or Tiepolo.

And indeed is there such a thing as an essence? Complicating the suggestion carried by the title, there are fascinating observations in the text about the rich influences and unexpected experiences—good and bad—that came to make up Native American art works. We learn here that working with silver was a skill brought up with Spaniards from Mexico, and the silver itself, in the form of coins, was the material in which many Native Americans were paid by the railroads for which they worked. Finally, paradoxically, being restricted to life on reservations was a condition for making art. To quote from the catalog, “Facing life on the reservation, the Navajos settled into an existence that allowed for an increased focus on traditional art forms.”

What is striking about Barnes is how much he did see, feel, and care about what were to him new, strange works of art. Indeed, contrary to the words about his distance, he immersed himself in what he saw—writing to Matisse on Feb 10, 1931, wishing he had been there to see the Indian dance:

“They take this very seriously and one can see the deep meaning it has for them . . . . It was an unique experience for me & I was sorry you were not with me to see the marvelous spectacle.”

It is appropriate that in 1932 Matisse painted his The Dance for Barnes.

Svetlana Alpers, an artist, critic, and renowned art historian, is professor emerita of the history of art at the University of California, Berkeley and a visiting scholar in the Department of Art History at New York University.