By David Madden

As if I witnessed in person each episode, Of Time and Knoxville is one of the most moving memoirs I have ever read, so real that I can revisit each scene readily at will.

Born in 1872, Anne Wetzell Armstrong was 13 when she, her parents, and brother and sister arrived in Knoxville, Tennessee, in 1885 from Grand Rapids, Michigan. I am reminded that in the unique memoir of her childhood, The One I Knew the Best of All (1893), Frances Hodgson Burnett tells the story of coming with her family from England after the Civil War to live in Knoxville, where her experiences formed the basis for The Secret Garden, and where she began her internationally famous writing career.

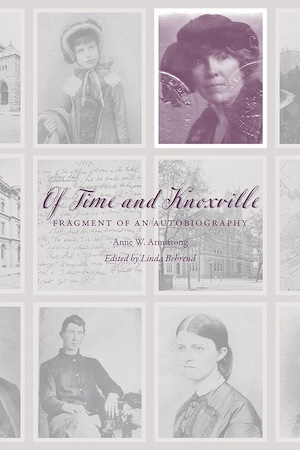

Armstrong began writing Of Time and Knoxville, her 480-page “fragment of an autobiography,” in 1947 and finished it before her death in 1958 at age 86. It is a “fragment” because in the “Thirty Years After” final chapter she only summarizes her life during the three decades between 1902, when she was 25 and 1928. The editor, Linda Behrend, provides a brief “Epilogue” about the rest of Armstrong’s life; her documentation superbly enhances the richness of Armstrong’s memoir.

Armstrong published, anonymously, the autobiographical novel The Seas of God (1915); This Day and Time (1930), reputedly the first novel to deal realistically with an Appalachia community; and a few articles about women in business, based on her work life.

“The heart knows its own climate when it finds it,” Armstrong writes, “and where I had always wanted to be—from the beginning—was Knoxville.” She declares often that each person, male and female, young and old, parents, brother and sister, boyfriend, lover, husband, girlfriend, house, neighborhood, school, teacher, book, writer, “made an instant and lasting impression on me.” Compulsively, she repeats that refrain throughout. “To this day, wherever I am,” living in Chicago, New York, Asheville, and Bristol, “the center of my universe” is still Knoxville. “Always somewhere in the back of my thoughts,” some reminder “can recreate for me . . . the Knoxville of my youth.” Her sustained desire to revisit Knoxville, her first great love, “was like a gnawing hunger.” A profound delineation of the nature of memory, her memoir “is a tissue . . . woven of memory, legend, of myth, of gossip . . . of dreams.”

The reader strolls unhurried through a gallery of the many young men, especially the university students, who courted her; and prominent women, old and young, her many girlfriends, especially lovely Laura, famous in Paris, where she was doomed to die of unknown causes.

Fully and vividly, Armstrong describes Knoxville events: a lynching at the bridge; a horrendous train wreck, fatal to many; the deaths by drowning of her beloved brother and her father; her little sister suddenly leaving the family; her illnesses; her student and teaching episodes. She recalls and renders in Proustian detail members of her family and all the other players in a life quiet and tumultuous by turns, a life in which houses, especially Bleak House, named after Dickens’ memorable novel, played major roles. Poor and rich neighborhoods, where she visited or lived, in north, south, west, and east Knoxville, were almost as vibrantly alive as their inhabitants. She “never lost a sense of joy at the sight of” the old churches, the old opera house, the Gay Street Bridge. She was poor, but she was a frequent visitor in houses of the most important families, her attitude being a combination of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s admiring comment, “The rich are different from you and me” and Hemingway’s response, “Yes, they have more money.”

In a variable style, she vividly expresses her feelings and convictions about sex, religion, her visions and attitudes about her life and about the lives of family members, friends, neighbors, and enemies. From early childhood on, she escaped the vise-like grip of small-town religion, scorning religion as a colossal, illogical bore, “utterly and absolutely dead,” while regarding the Bible as “the most fascinating and glorious book in the world.” Listening to Julia Ward Howe preach was “a mental stimulus . . . a challenge.” She learned about “the nobility, the redeeming force, of work, that a task once taken up should not be laid down.”

Armstrong grew up when “the age of promiscuous ‘petting’ had not yet arrived.” As a teenager, she was so ignorant that she failed to conceive of how the female body could produce a baby. A stolen kiss struck her as “a slightly terrifying if ecstatic experience.”

Her first marriage was such a sordid, prolonged awfulness that it defies a short summary. Going into “the wider world” as a wife turned out to be one room over a saloon on Whiskey Row in Snohomish, Washington and a small cottage in Fargo, North Dakota where she cared for her baby (the only child she ever had, who died when his plane crashed). Her family disowned her for a while when she eloped with a very intelligent man who was unable to “make love” to her without first beating her. “I faced a future for which I had no plans and saw only a dark disordered waste stretching ahead of me interminably.” Even as she was caught in a web of her own weaving, she was in “a constant state of intoxication,” of “sheer animal spirits,” of “a huge zest for living.” She resolved not to wait for experiences to come to her, but to go out and seek them. “Live, live all you can! Live, before it’s too late.” “My sense of adventure never left me.”

Armstrong is scornful of the fact that Knoxville once supported 21 saloons but not one library. From her teens, she was an intellectual, with the sensibility of a poet, and she became an innovative teacher. She regarded The Letters of Jane Webb Carlyle—wife of Thomas—as the “greatest collection of letters ever produced by a woman.” As she describes her vivid memories of the many writers she read and taught and who inspired her to write, Armstrong conveys a rich sense of the development of major facets of her complex self. Among them were powerful poets Walt Whitman and Robert Browning; novelists George Eliot, Thomas Hardy, Balzac, George Sand; and nonfiction thinkers John Dewey, Thorsten Veblen—“the strongest influence on my future thinking—on my entire social outlook”—and Jane Addams, who invited her to Hull House.

Armstrong is one of the most severe critics of Knoxville. She excoriates “a completely denatured history of Knoxville,” calling her own a “profane” history that spares nobody and no place. For instance, she creates a scathing portrait of intellectual and social luminary Mary Temple, “perennial laughingstock,” who wanted to marry Colonel Tom Williams, Tennessee Williams’ grandfather. By comparison, she lovingly describes Louise Armstrong, “the bewitching . . . dashing young mistress of Bleak House,” who became her mother-in-law. Bleak House cast a spell over her that lasted the rest of her life. “All the romance, the glamour I had found in Knoxville and which had dominated my youthful imagination” from the first day and for the rest of her life as the wife of the love of her life, Bob Armstrong, “were distilled now in that house,” with its Civil War past as General Longstreet’s headquarters, now a major museum of the Confederacy.

Given the nearly 500 pages in hand, readers may be amazed that Armstrong sustains a flowing pace, enhanced by effective transitions, two of her many stylistic and technical achievements. Her style is sometimes a cross between Henry James and Sinclair Lewis, sometimes even more lyrical than her friend Thomas Wolfe’s style.

As quotations on three large plaques embedded in concrete in the open space left by demolition of the historical market house attest, Knoxville natives James Agee, Cormac McCarthy, and David Madden described that edifice, but Anne Armstrong deserves a plaque for her own more masterful description, rendered in five pages of finely detailed, thrillingly theatrical, and morbidly ghoulish sights and sounds, human and zoological images.

David Madden (ΦBK, University of Tennessee) is Louisiana State University Robert Penn Warren Professor Emeritus. Momma’s Lost Piano: An Impressionistic Memoir is Madden’s latest work. My Creative Life in the Army, a memoir, is under consideration.