By Fred H. Lawson

Shortlisted for ΦBK’s 2025 Ralph Waldo Emerson Award

Two events in the mid-nineteenth century sparked renewed interest in understanding the genesis of humankind. The first was the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1859; the second was the discovery three years earlier of a fossilized skull in the Neander Valley outside Dusseldorf, Germany, which exhibited notable discrepancies with the skulls of contemporary humans. The widely held, albeit it wildly wrongheaded, conception of natural selection as a linear progression from simian to homo sapiens prompted influential scientists in Europe and the United States to conclude that the new-found creatures represented an intermediate step in the ascending ladder.

More important, Stefanos Geroulanos shows that the discussion of the place of Neanderthals in the rise of humanity intersected with ideas about the hierarchy of races that pervaded European intellectual and political arenas. The eminent British geologist Charles Lyell reported in his authoritative textbook The Geological Evidences for the Antiquity of Man that the size of the Neanderthals’ skull was “very nearly halfway” between that of a “European” and that of a “Hindoo”. Lyell’s colleague William King thought Neanderthals ranked just below the people of the Andaman Islands, whom he considered to be the world’s “most backward” inhabitants.

Such comparisons resembled earlier disquisitions on the part of European social and moral philosophers. “In 1724,” Geroulanos reports, “the Jesuit missionary and proto-ethnologist Joseph-Francois Lafitau published a fascinating and tedious four-volume study of The Customs of the American Indians Compared to Those of Primitive Times.” Shortly thereafter, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and John Locke intimated that the inhabitants of North and South America prior to the arrival of Christopher Columbus exemplified the state of nature that had existed before the emergence of governmental institutions. Rousseau in fact claimed that the “Caribs of Venezuela, of all existing peoples, are the people that until now has wandered least from the state of nature.” If one wished to know what things were like at the dawn of humanity, one could observe life in the New World. Or in central Africa, or on the islands of the Indian Ocean and the South Pacific.

The Invention of Prehistory is filled with vignettes and anecdotes of how European (and a few American) scholars, public intellectuals and artists have interpreted and represented prehistoric humanity. It is reminiscent of Edward Said’s provocative survey of Orientalism, in that it presents a not-too-subtle critique of an impressive range of writings, paintings, and other representations that propelled discourse and public policy-making with respect to an important topic. Like Said, Geroulanos makes no attempt to empathize with or excuse what he considers to be woefully distorted viewpoints. The book is not quite condescending, but it does at times seem imperious.

It also never really delivers what the title promises: an analysis of “the invention of prehistory” (clearly an allusion to Eric Hobsbawm’s path-breaking explication of “the invention of tradition”). Geroulanos remarks in passing, on page 85, that “as a field, prehistory (Vorgeschichte, prehistoire) was born amid the political and intellectual chaos of the 1860s.” But very little of the text deals with that crucial decade, and whatever political circumstances might have shaped the birth of the field are left unaddressed. Matters related to the empires mentioned in the subtitle pop up sporadically, but if readers expect a cogent argument connecting the dynamics of European imperialism to the development of modern thinking about prehistory, they will come away disappointed.

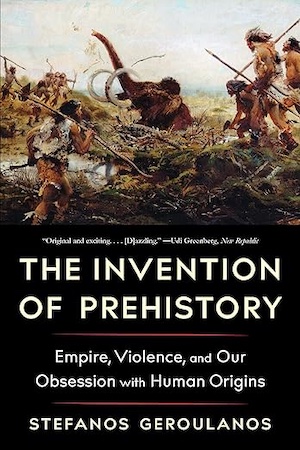

Instead of a unified monograph, The Invention of Prehistory offers a collection of short commentaries on various aspects of “how we and other moderns talk and think about the deepest past.” Friedrich Engels’s speculations about private property and the family receive careful consideration. Changes in popular depictions of Neanderthals across the late 19th and 20th centuries are surveyed. How European nationalists—including Germany’s National Socialist Democratic Workers’ Party—deployed the image of invading hordes is vividly described. And the cave paintings of southern France are accorded somewhat more sustained treatment. Taken together, these sketches show what a tortuous path has led to our present vantage point on earliest humanity.

Fred H. Lawson (ΦBK, Indiana University) is Professor of Government Emeritus of Northeastern University.