“The condition of our survival in any but the meagerest existence

is our willingness to accommodate ourselves to the conflicting

interests of others, to learn to live in a social world.”

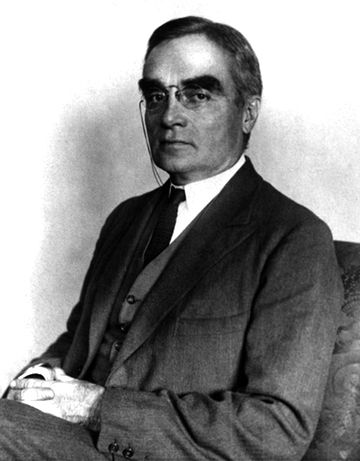

— Learned Hand

By Ben Beito

Learned Hand was among the most innovative judicial men of law in American history. Graduating Phi Beta Kappa from Harvard with a philosophy degree in 1893, and then Harvard Law school, he was appointed a federal district judge of Manhattan and eventually became Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals of the Second Circuit in 1939.

In “Master of Restraint,” a 1994 New York Times review of Learned Hand: The Man and the Judge, John T. Noonan, Jr., notes the three ways by which Hand made his contributions as a Judge: “by the careful consideration of the facts before him, a thoughtful review of relevant precedent, and a reasoned explanation of why he reached the result he did.” In maintaining a balanced philosophy, Hand understood that there was no formula to successful justice as much as fitting a legal result to the facts while considering the possibility of generalizing the result.

The loss of his father at age fourteen greatly affected Hand’s psyche during his coming of age. Hand was haunted by the pressure to live up to an idealized image of his lawyer father, who was briefly a New York court of appeals judge. His worrywart mother touted his deceased father’s idealized image, which further agitated Hand’s inner guilt. While this would certainly be an emotional impediment for most, perhaps Hand was able to channel this guilt to fuel his longstanding intellectual success.

Hand published two popular books expounding on his philosophy of law. The first, The Spirit of Liberty (1953), is a compilation of essays by Hand at various points in his career. In one of his essays, “The Speech of Justice,” Hand eloquently elucidates how the law relates to society and how a judge must effectively interpret that relationship.

His second book, The Bill of Rights (1958), provides a multitude of insights about the seemingly simple rights of every American and how they operate within the judicial context. Hand notes that for proper interpretation of any individual case it is necessary to add unexpressed provisions to powerful texts like a constitution: “since they are designed to cover a great multitude of necessarily unforeseen occasions, [constitutions] must be cast in general language, unless they are constantly amended.”

Hand’s demeanor in conversation reflected a personality fit for enthralling communication both inside and outside of the courtroom. With regard to this, Noonan notes in “Master of Restraint”: “There was so much affable, urbane charm in the expression of his face that the person to whom he was listening could not possibly feel inhibited or constricted.” It seems as though he had a distinct combination of social and linguistic brilliance that played a huge role in shaping his successful law career.

Perhaps one other defining characteristic that set Hand apart from most judges, according to the article “Judge Learned Hand” in the Harvard Law Review, is that: “He is aware as few judges have been that whatever may appear on the smooth surface in earlier opinions, law must deal mainly with probabilities, not certitudes.” This virtue allowed him to be a hub of applied wisdom in his judicial practice.

Hand lived a prolific, long life dying in 1961 at the age of 89. His term as a federal judge trumps any other in length to date.

Ben Beito is a senior at St. Olaf College majoring in Architectural Studies, a program he designed himself. St. Olaf College is home to the Delta of Minnesota Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.