By Indira Ganesan

“When the world sleeps,” Nehru said in 1947, on the eve of independence, “India will awaken to life and freedom.”

That was India at midnight.

Were he to come to my daughter’s India, he might say otherwise. While the world sleeps, Indians come of age and holler.

This is India at noonday.

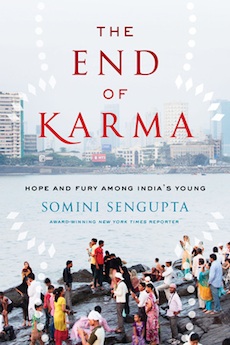

So begins Somini Sengupta’s insightful look at Indian youth in The End of Karma: Hope and Fury Among India’s Young. I can’t convey the excitement I felt in 1995 when I first saw a byline by Sengupta on The New York Times front page. I think I looked at the name several times. A journalist who now covers the United Nations for The New York Times, she was once the bureau chief in New Delhi for the paper, the first journalist of Indian descent to hold the position. 1995 was a good year for South Asians in the American media. We had the wonderful Daljit Dhaliwal on ITN, and of course The Simpsons had an Indian character, a mixed blessing stereotypically voiced by Hank Azaria; It would be years before South Asian doctors actually appeared on medical serials on TV.

In this book, Sengupta (ΦBK, University of California-Berkeley, 1987) gives us a history of modern India, an independent secular nation that would, fifty-plus years after her independence, elect a vehemently pro-Hindu party and PM to govern. India becomes home to a rising technology boom. By 2011, “more Indians had a cell phone than a toilet,” writes Sengupta. It has become a “fifty-fifty” democracy, in the words of historian Ramachandra Guha; it works about half the time, and it is full of contradictions. While the middle upper classes retreated behind gated communities, Sengupta reminds us that two-thirds of Indians sustained themselves on less than $2 a day. Finally, one million young people turn eighteen every month. Who are these young people? Sengupta chooses seven under thirty-five and their tales.

Sengupta defines karma in the “colloquial sense—as destiny.” But she addresses as well as push felt by the young to “break free of its past.” She presents a series of stories about these noonday children, who will not tolerate the status quo, who push to change their lives, and some who discover slowly that the country “conspires to fail them. . . at every step of the way.” Yet this doesn’t stop the ambition to push away the past, a past full of violence and inequity, caste and religion, and want to do better.

Sengupta gives us seven individuals with their own sets of privilege and set-backs, young women and men who try to rise up despite a country that wants to beat them back down. One is a student drawn into a cult that gives him sweets and company; another is a man who marries for love outside caste only to be killed by his wife’s brother who then kills his own sister, in an act of honor. We witness two girls see their mildly critical political Face Book posts escalate into arrest. A woman who becomes a casual killer and a Maoist. Everywhere, economics, gender, and class play a part in opportunities, but then, they do, the world over. Finally, Sengupta addresses the horrific bus rape in 2012, and she notes the activism that resulted.

Being a woman in India without a child is an oddity, she says, in the most amusing part of the book:

A pedicurist might look up at you in casual conversation and say, “Madame, no children? Why?”

The shopkeeper might probe casually, “Is it Sir who has the problem or you?”

The gynecologist might shout across the packed waiting room with your chart in her hands: “Still ovulating, no?”

I was on the floor with laughter, having encountered my share of “Are you married? Why not?” from South Asian cab drivers, one of whom cheerfully proposed, despite our twenty-year age gap. It is a moment of light humor in a clear-eyed serious telling of what it means to be young in India today.

Seven narratives won’t encapsulate India, she says, but these are stories that haunt her, that she thinks about in terms of the India her daughter will grow up in. It is a sobering look, but not without hope.

Novelist Indira Ganesan was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa at Vassar College in 1982. Her books include The Journey (Alfred A. Knopf, 1990), Inheritance (Alfred A. Knopf, 1998) and As Sweet As Honey (Alfred A. Knopf, 2013).