Shortlisted for the 2016 ΦBK Christian Gauss Award

By Megan Snell

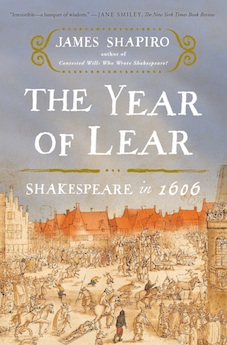

In the aftermath of a failed terrorist attack, with a new king attempting to unite Britain’s countries amid suspicion of supernatural and papist influences, Shakespeare probably had a lot on his mind in 1606. James Shapiro’s The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606 argues that it was because of, not in spite of, this turbulent context that Shakespeare produced some of his greatest plays: King Lear, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra. Though Shakespeare’s works are often called “timeless,” Shapiro shows how history and Shakespeare’s writing “are so closely intertwined that it’s difficult to grasp the meaning of one without the other.”

A sequel of sorts to his previous book, A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare: 1599 (2006), Shapiro again focuses on one consequential year in the life of Shakespeare and his country. Against the backdrop of national issues, we follow Shakespeare’s own whereabouts as best we can, a tricky task for a man who left little biographical evidence behind. From a landlady possibly killed by plague to a daughter who refused to receive communion, Shapiro traces how the larger concerns of the country often hit Shakespeare close to home, and subsequently resonate in his work.

Shakespeare today is so strongly associated with the iconic Queen Elizabeth I that it might be easy to forget that she died halfway through his career. Starting in 1603, Shakespeare wrote some of his most famous plays under the eye of a different monarch, James I. Recently arrived from Scotland, James raised Shakespeare’s status when he chose his troupe, formally patronized by a nobleman (the Lord Chamberlain), to be the official company of the reigning monarch, the King’s Men. Yet tastes and fashions were changing. Masques, expensive musical spectacles that featured lavish costumes and courtier performers, now captivated the royal court. Struggling to write hits after James’s coronation, Shakespeare was at risk of becoming a relic of the Elizabethan past. Ultimately, though, Shakespeare learned “to speak with the same acuity about the cultural fault lines emerging under the new and unfamiliar reign of the King of Scots.”

It is these “fault lines” that Shapiro elucidates in Year of Lear. While petitioning parliament to unite Scotland officially with his new kingdom of England, James spent his time investigating “real” and fraudulent demonic possession. Indeed, he had reason to suspect that some kind of evil forces threatened his realm. Exposed only by the theatrical arrival of a letter, the Gunpowder Plot of the previous year had attempted to assassinate James and destroy the government by detonating the House of Lords. Though the gunpowder was never lit, the hypothetical fear of what might have been caused very real effects that haunted the following year and beyond. Shapiro thrillingly details the foiled plot in London and tracks the ensuing hunt for the Catholics held responsible, which included a dramatic horse theft near Shakespeare’s hometown of Stratford. Later trials of Jesuit priests found hiding in recusant homes created a public paranoia of Catholic “equivocation”: the ability to say one thing while hiding the truth through ambiguous wording, deliberate omission, secret gestures, or, most troubling of all, “mental reservation,” a religiously sanctioned deceit in which “your words and thoughts were at odds.” All the while, the threat of deadly plague lingered, ready to strike again in the summer of 1606.

Shapiro’s book is ultimately a source study, providing compelling insight into Shakespeare as a talented reviser of preexisting literary texts and observer of his contemporary social and political environment. Though it remains impossible to know exactly how the playwright felt about what was happening in his country, Shapiro’s accessibly presented research illuminates the potential mindset of his audience; exposing why, for example, for Shakespeare’s audience, already familiar with a vastly different ending to the old “King Leir” story, this new version was particularly devastating. In the detailed historical context that Shapiro maps, we find new significance in Lear’s division of Britain, the weird sisters equivocal riddles to a Scottish king, and the nostalgia and admiration for a strong queen. For those ready to explore the shift from Elizabeth’s England to James’s Britain, Shapiro is a deft guide to Shakespeare’s great works produced in the critical year of 1606.

Megan Snell (ΦΒΚ, Colgate University, 2012) is a Ph.D. student in the Department of English at the University of Texas at Austin. The University of Texas at Austin is home to the Alpha of Texas Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.