By Jay M. Pasachoff

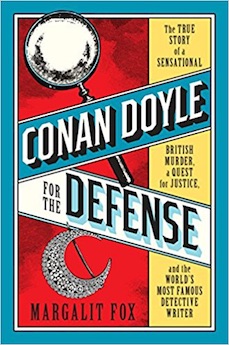

Margalit Fox, long skilled as an obituary writer for The New York Times, has turned her attention to a true case allied to the fictional case of the world’s most famous consulting detective, Sherlock Holmes. In her book, ostensibly about the dismaying case of the false conviction of Oscar Slater a hundred years ago, we learn about a wide variety of historical and philosophical matters.

Slater was a foreigner in England, and a Jew at that, so when a particularly vicious murder of an old woman took place and a potential link to him was found, he was pursued. Indeed, without his knowing it, his innocent trip to New York en route to accept an invitation to work in San Francisco, increased suspicion on him and he was arrested on arrival in New York on the steamship Normandy.

A diamond-studded broach had been taken during the murder, which took place while the woman’s assistant was out for a few minutes to pick up a newspaper. And Slater had pawned a broach set with diamonds. But even when the assistant identified the broach as different from her late employer’s, and even when the police discovered that the broach had long been in Slater’s possession and had been pawned by him numerous times over preceding years, they didn’t drop the case.

So Slater innocently went along with his extradition, convinced in his innocence. But he was convicted and sentenced to hard labor in a Scottish prison. Only when Arthur Conan Doyle turned his attention to the case was Slater eventually released.

We learn much in digressions, a minor fact such as the reason that his father added “Conan” to the Doyle name for his son and major facts such as the way Conan Doyle learned about reasoning from observations of apparent trivia from Dr. Joseph Bell during his training as an ophthalmologist. We learn that though Holmes’ method is called deduction, it is more likely induction or even abduction, and true and false syllogisms are provided by way of explanation.

We also learn about the history of policing, and are brought to ponder some of the deficiencies that persist even to today, such as choosing suspects and then finding evidence instead of the reverse. Finding Slater as a suspect and pursuing him in spite of the prime evidence, the broach, falling away reminded me independently of the Dreyfus case, as it also reminded Fox.

In her New York Times Book Review piece about the book, detective-scholar author Judith Flanders criticizes the incompleteness of the discussion of Conan Doyle’s life, such as his treatment of his first wife. Be that as it may, we learn a lot about Conan Doyle and about his history with Sherlock Holmes, including his apparent death and then his reappearance, with the individual stories, novels, and dates discussed.

How Conan Doyle could have reasoned so thoroughly on forensics, though wound up believing in fairies is another matter.

My wife and I heard the book read aloud on Audible, with the reader—Peter Forbes—switching flawlessly to an American accent or other accents when needed from his basic Scottish.

I am glad to recommend Margalit Fox on Conan Doyle, on Oscar Slater and his case, and on philosophical and forensic matters.

Astronomer and author Jay M. Pasachoff is the director of the Hopkins Observatory and Field Memorial Professor of Astronomy at Williams College. He is a Visitor in the Carnegie Observatories. Williams College is home to the Gamma of Massachusetts Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.