Shortlisted for the 2018 Ralph Waldo Emerson Award

By Louis J. Kern

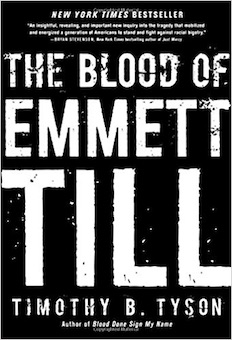

In recounting the horrific details of the torture and murder of Emmett Till (August 28, 1955), Tyson contextualizes the lynching as a reaction to the inception of the modern Civil Rights movement, driven by organizations like the Regional Council of Negro Leadership (1951). The Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Topeka Board of Education (May 17, 1954) and Brown II (May 31, 1955) led to widespread Southern determination to resist and impede the progress of “all deliberate speed.” The killing was hardly unusual in the era; a few weeks prior George Lee and Lamar Smith, black voter registrants, had been assassinated. Till’s murder was not politically motivated, but expressed fears of integration and social equality. The mythical fear of the black sexual predator threatening the purity of southern white womanhood, the folk pornography of lynchings since the slave era, was invoked to exculpate a criminal act of resistance to social equality.

The Citizens’ Council, founded in Indianola, Mississippi (July 11, 1954), that sought to interdict black voting and desegregation, defended Till’s killers. It spread throughout the South, buttressed by Thomas Brady’s speech and later pamphlet, Black Monday: Segregation or Amalgamation. America Has Its Choice (October 28, 1954). With chilling prescience, Brady had declared that a “supercilious, glib young Negro . . . will perform an obscene act, or make an obscene remark, or a vile overture or assault on some white girl” that would trigger a wave of violence grounded in what W, J. Cash termed “the Southern rape complex”.

Tyson provides details of the gruesome murder, but the real strength of this volume lies in its use of the trial transcript (State of Mississippi v. J. W. Milam and Roy Bryant), the lawyers notes on and the author’s personal interview with Carolyn Bryant (the putative victim). He highlights the heroism of prosecution witnesses subsequently forced to leave Mississippi in fear of their lives. Of central importance was Mamie Bradley’s courageous decision to exhibit the open casket of her son and her appearance in the dozens of protest rallies that followed. As Tyson demonstrates, the mass movement that developed was the catalyst for the sit-ins, freedom rides, voter registration drives, and the Birmingham bus boycott—the emergence of the modern Civil Rights movement.

An all-white jury acquitted Till’s killers as defenders of racial purity. It is at this point that Tyson provides an important revision to the history of the case. In an interview, Carolyn Bryant told him that she lied on the witness stand, that Till had never touched her, and that he had done nothing to merit the horrible death he experienced. While much of the country was appalled by the murder and the acquittal, the South drew inward in a defensive posture that reinforced its determination to defend segregation. And the violence did not stop. Medgar Evers who had led the NAACP response to the case was murdered by a member of the Citizens’ Council in June 1963. Nor were children exempt from terror; three months later four girls were killed in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham. Then, in April 1968 Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated.

Still, as Tyson makes clear, the struggle goes on in the Black Lives Matter movement and the challenges to racially skewed mass incarceration. If the “national racial caste system” is to be abolished, he concludes, “all of us must develop the moral vision and political will to crush white supremacy” and to acknowledge the legacy of “genocide, slavery, exploitation, and systems of oppression” of our tragic history.

Louis J. Kern (ΦBK, Clark University,1965) is professor emeritus of history at Hofstra University. Hofstra University is home to the Omega of New York chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.