Reviewed together with The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. Edited by John F. Marszalek, with David S. Nolen and Louie P. Gallo. Belknap/Harvard University Press, 2017. 784 pages. $39.95.

By Allen D. Boyer

A horseman who rode superbly and drove his buggy like a demon. A loving family man; a hard-working, easy-going farmer. An alcoholic with no head for business. Of all American generals, the best at handling setbacks—“not a retreating man,” as Robert E. Lee warned. An American everyman, a president who told jokes on himself. A writer who mastered his craft as he lay dying.

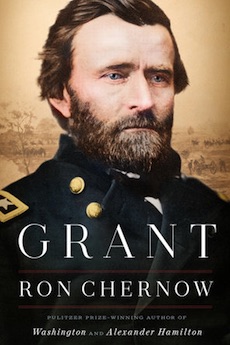

In his admirable biography of Ulysses S. Grant—a book that is solid in every sense, long, fact-packed, masterful, readable—Ron Chernow sketches these profiles, and more, of the man whose worn but resolute face looks out from the fifty-dollar bill. Another new book on Grant is equally notable. A handsome new edition of Grant’s eloquent Memoirs, edited and carefully annotated by John Marszalek, does honor to a work that has been hailed as the best presidential autobiography and the greatest military memoir since Caesar’s Commentaries.

Alcoholism shadows these books, as it shadowed Grant’s early career. Grant started drinking as a young lieutenant, after the Mexican War. He could not touch alcohol without becoming completely, convivially, helplessly drunk. In 1854, after two lonely years in forts on the West Coast, far from his family, alcoholism gripped him, and it cost him his commission.

The Civil War offered Grant a second chance. For Grant did not drink all the time, and his self-control, although not absolute, could be iron-clad. He did not drink when he was with his wife. He did not drink, Chernow writes, “during combat periods, when he was actively engaged and shouldered responsibility.” Grant captured Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, and defeated a Confederate army at Shiloh. He captured Vicksburg and freed the Mississippi, and Lincoln brought him east to fight Robert E. Lee.

Grant thought political ties encumbered a general; men who obtained command through political influence were reluctant to employ their own judgment, preferring to await “direct orders from [their] distant superiors.” Yet he understood the politics of the war, perhaps as well as Lincoln – knew that many politicians and voters were ready to negotiate a peace with slave-owners. His time in Mississippi had changed his understanding of the war.

Grant blamed the fire-eater politicians of the South for starting the war. Across the South, as Grant saw it (and Karl Marx, looking on from London, thought the same), the slave-owners had seized power after Lincoln was elected, silencing opposition and pushing through secession ordinances. “The Southern slave-owners believed that, in some way, the ownership of slaves conferred a sort of patent of nobility—a right to govern independent of the interest or wishes of those who did not hold such property.”

For the first year of the war, up through Shiloh, Grant had thought that the slave-owners’ grip on the Southern states was tenuous and would easily be crushed. “But when Confederate armies were collected which not only attempted to hold a line further south, from Memphis to Chattanooga, Knoxville, and on to the Atlantic, but assumed the offensive . . . then, indeed, I gave up all idea of saving the Union except by complete conquest.” “Up to that time,” Grant wrote, he had scrupulously protected the private property of citizens “without regard to their sentiments, whether Union or Secession.” After Shiloh, he ordered a change. “Supplies within the reach of Confederate armies I regarded as much contraband as arms or ordnance stores.”

After Shiloh, Grant and his men fought for months in North Mississippi. By December Grant was in Oxford, advancing toward Vicksburg. Confederate cavalry raided Holly Springs, thirty miles north, and destroyed the supplies that Grant had amassed. Grant halted his drive south, but he was unfazed. He sent out foragers, “all the wagons we had,” to collect provisions along the route back to the Tennessee border.

“The news of the capture of Holly Springs and the destruction of our supplies caused much rejoicing among the people remaining in Oxford. They came with broad smiles on their faces, indicating intense joy, to ask what I was going to do now without anything for my soldiers to eat. I told them that I was not disturbed; that I had already sent troops and wagons to collect the food and forage they could find for fifteen miles on each side of the road. Countenances soon changed, and so did the inquiry. The next was, ‘What are we to do?’ My response was that we had endeavored to feed ourselves from our own northern resources while visiting them; but their friends in gray had been uncivil enough to destroy what we had brought along, and it could not be expected that men, with arms in their hands, would starve in the midst of plenty. I advised them to emigrate east, or west, fifteen miles, and assist in eating up what we left.”

There is Grant’s style and perspective: direct, plain-spoken, sharp as a jest but delivered without a smile, without contempt and without any false note of apology.

In May 1864, Grant fought Lee in the Battle of the Wilderness, and suffered heavy losses. Previous Union commanders had used such losses as an excuse to break off fighting. Grant, instead, drove on; he meant to fight until the war came to a close. He kept moving, forcing a battle at every river and crossroads, fighting almost daily. When he could not reach Richmond from the north, he slipped loose and marched and threatened it from the south. Within eight weeks Grant had done what no Union commander had been able to do in three years: immobilize Robert E. Lee. He forced Lee’s army to entrench itself at Petersburg, besieged it there for nine months, and finally trapped it when it tried to escape.

It had been a close-run thing, as Grant realized: “the Nation had already become restless and discouraged at the prolongation of the war, and many believed it would never terminate except by compromise.” Even in March 1865, he took particular care with the orders under which Phil Sheridan’s troops would set Lee on the run, “knowing that unless my plan proved an entire success it would be interpreted as a disastrous defeat.”

This is the side of Grant that Chernow shows most often. The general who opened what would become the Freedmen’s Bureau (on the Tennessee-Mississippi border, in the fall of 1862) was the one president who supported Reconstruction. Elected president in 1868—thousands of new black voters helped carry the South for him—Grant ended his inaugural address by calling for ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment. As authorized by the Ku Klux Klan Act, he broke the power of white nightriders by suspending habeas corpus and sending in federal troops. Scandals plagued his administration, but he held the line for eight years. Only the contested election of 1876 brought an end to Reconstruction.

To the former president remained one last debacle and one last recovery. Grant allowed his money and reputation to be used by a promising young financier, Ferdinand Ward. As Charles Ponzi would later do, Ward paid out early investors with money paid in by later investors. Ward’s scheme collapsed in May 1884. Grant found himself once more almost overwhelmed by fate. He had cancer in his throat, and faced a perfect storm of further afflictions. Once more, with coolness and quiet determination, Grant found something of a way out. He had earlier resolved not to write his memoirs. He changed his mind, and signed a contract with Mark Twain that guaranteed him 70% of the net profits.

As the biographer of Washington, Hamilton, J.P. Morgan, and John D. Rockefeller, Chernow knows first-hand the hard work Grant was doing. “Grant toiled four to six hours a day, adding more time on sleepless nights. For family and friends his obsessive labor was wondrous to behold: the soldier so famously reticent that someone quipped he ‘could be silent in several languages’ pumped out 336,000 words of superb prose in a year. . . . [Twain] was agog when Grant dictated at one sitting a nine-thousand-word portrait of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox ‘never pausing, never hesitating for a word, never repeating—and in the written-out copy he made hardly a correction.’”

The general finished The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant scant days before he died. With their lapidary style, common sense, and generosity, his recollections gave Americans reason to once more honor their author. Chernow’s biography and Marszalek’s edition of the Memoirs offer the same opportunity.

Allen D. Boyer (ΦBK, Vanderbilt University, 1977) is a lawyer and writer in New York City. His fifth book, Rocky Boyer’s War, has recently been published by the Naval Institute Press. Portions of this review were previously published by HottyToddy.com. Vanderbilt University is home to the Alpha of Tennessee Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.