By Allen D. Boyer

This is a chronicle of the last days of Jim Crow. An energetic memoir by Pauline Estelle Merry, it recalls a childhood in the shadow of racial segregation, being “a young colored girl growing up in the 40s and 50s in St. Louis, in an area called The Ville.” It is a study of when black people could bend the color bar—how it was to live in a society that was never equal, but also never completely separated.

In St. Louis, the public library freely issued library cards to black readers. City parks and auditoriums always admitted black citizens. The Forest Park Zoo was always open to black people (the privately-owned amusement park next door, never). Merry could study music with a white teacher, even if she had to drop off a double bass at the back door.

At the American Theater, black people had to sit in the balcony. Merry’s mother decided “that she and I would only attend events in facilities where we could sit where we wanted.” At the city’s Kiel Auditorium, Merry and her mother might be the only black opera-goers, but they could sit anywhere. She heard the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, the Metropolitan Opera, Marian Anderson, Roland Hayes, and Paul Robeson (also Adlai Stephenson, on a campaign tour). She heard gospel choruses from her mother’s family on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. A practiced pianist, Merry reflects, ironically, that she was versed in every kind of music, except jazz.

Merry remembers the Ville as a prospering community.

“It was a middle-class neighborhood that could boast of well-kept houses, green lawns, and precious trees whose residents were a wonderful mixture of educated people, like my parents, and working class skilled laborers, like our next door neighbors, the Sloans. Mr. Sloan worked at the steel mill and Mrs. Sloan had her own beauty parlor . . . . I dated the son of the only Black fireman in the city. He lived up the block from my house.”

The Ville was a place where a graduate student might show up, looking for printmakers who had trained in a WPA studio project. Black colleges formed a network of connections and support; people from Lincoln University and Meharry Medical College traded news of school friends. When Merry’s family visited Maryland, they took the railroad to Chicago and then arced east to Philadelphia. By traveling north of the Mason-Dixon Line, they could sit in any carriage and eat in the dining car: “The Black waiters were very nice . . . nicer than they had to be, perhaps because they were proud to see us there.”

There were familiar human frictions. Merry’s high school classmates knew her as the daughter of a teacher renowned for strictness. Her mother kept her distance from the local chapter of Jack and Jill because she feared her décor might be found wanting.

This book traces Merry’s growing awareness of racial injustice. “Frankly,” she remembers thinking, “I still had no real sense of being deprived. Just because I couldn’t go to the Fox Theatre didn’t matter all that much to me. That I couldn’t go to school with white kids didn’t matter to me at all.” The more she understood, the more that changed.

Merry learned about racism in the Deep South from interviewing neighbors who had moved away from there. A white professor’s wife in Chestertown worked with her to research her family history in courthouse records. A black woman whom her father remembered from Tougaloo introduced her to the Congress of Racial Equality, the first step in a life that would take Merry across Europe and Tanzania and to a career as a college provost in California.

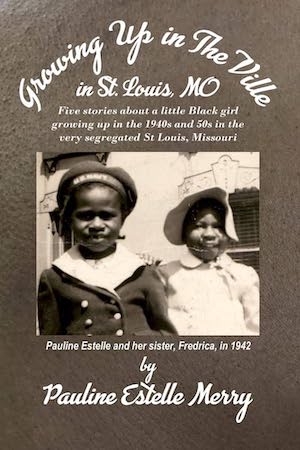

Merry calls this book “my younger self speaking.” Each chapter makes points and draws questions for other young readers. An epilogue sees Merry at 75, on a motorcycle in Africa, and unwinds into photographs of her family and the Ville. Quietly, but clearly, this measures the vast distance that little girl has traveled.

Allen D. Boyer (ΦBK, Vanderbilt University) grew up in Mississippi and now lives and writes on Staten Island. Vanderbilt University is home to the Alpha of Tennessee chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.